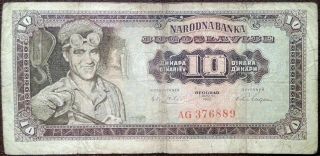

Yugoslavia Banknote - 10 Dinara - Year 1994 - Petar Petrovic Njegos - Civil War

Item History & Price

| Reference Number: Avaluer:10230573 | Country: Yugoslavia |

| Country/Region of Manufacture: Serbia | Circulated/Uncirculated: Circulated |

| Modified Item: No | Type: Banknotes |

| Year: 1994 | Certification: Uncertified |

SEE MY OTHER AUCTIONS

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

IF YOU ARE SATISFIED WITH SERVICE, PLEASE LEAVE US A POSITIVE FEEDBACK

HAVE A GOOD LUCK!!!

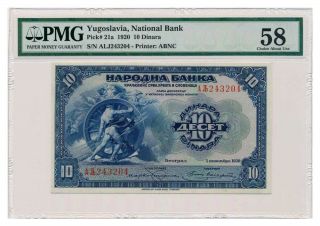

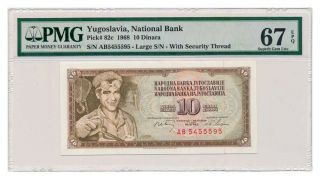

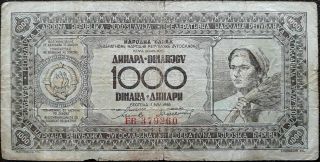

The dinar was the currency of the three Yugoslav states: the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (formerly the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes), the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia between 1918 and 2003. The dinar was subdivided into 100 para (Cyrillic script: пара). In the early ...1990s, there was severe and prolonged hyperinflation due to a combination of economic mismanagement and criminality. Massive amounts of money were printed; coins became redundant; inflation rates reached the equivalent of 8.51×1029% per year. The highest denomination banknote was 500 billion dinars; it was worthless two weeks after it was printed. This hyperinflation caused five revaluations between 1990 and 1994; in total there were eight distinct dinari. Six of the eight have been given distinguishing names and separate ISO 4217 codes.Under Tito, Yugoslavia ran a budget deficit that was financed by printing money. This led to a rate of inflation of 15 to 25 percent per year. After Tito, the Communist Party pursued progressively more irrational economic policies. These policies and the breakup of Yugoslavia (Yugoslavia now consists of only Serbia and Montenegro) led to heavier reliance upon printing or otherwise creating money to finance the operation of the government and the socialist economy. This created the hyperinflation. By the early 1990s the government used up all of its own hard currency reserves and proceded to loot the hard currency savings of private citizens. It did this by imposing more and more difficult restrictions on private citizens' access to their hard currency savings in government banks. The government operated a network of stores at which goods were supposed to be available at artificially low prices. In practice these store seldom had anything to sell and goods were only available at free markets where the prices were far above the official prices that goods were supposed to sell at in government stores. All of the government gasoline stations eventually were closed and gasoline was available only from roadside dealers whose operation consisted of a car parked with a plastic can of gasoline sitting on the hood. The market price was the equivalent of $8 per gallon. Most car owners gave up driving and relied upon public transportation. But the Belgrade transit authority (GSP) did not have the funds necessary for keeping its fleet of 1200 buses operating. Instead it ran fewer than 500 buses. These buses were overcrowded and the ticket collectors could not get aboard to collect fares. Thus GSP could not collect fares even though it was desperately short of funds. Delivery trucks, ambulances, fire trucks and garbage trucks were also short of fuel. The government announced that gasoline would not be sold to farmers for fall harvests and planting. Despite the government's desperate printing of money it still did not have the funds to keep the infrastructure in operation. Pot holes developed in the streets, elevators stopped functioning, and construction projects were closed down. The unemployment rate exceeded 30 percent. The government tried to counter the inflation by imposing price controls. But when inflation continued, the government price controls made the price producers were getting so ridiculous low that they simply stopped producing. In October of 1993 the bakers stopped making bread and Belgrade was without bread for a week. The slaughter houses refused to sell meat to the state stores and this meant meat became unvailable for many sectors of the population. Other stores closed down for inventory rather than sell their goods at the government mandated prices. When farmers refused to sell to the government at the artificially low prices the government dictated, government irrationally used hard currency to buy food from foreign sources rather than remove the price controls. The Ministry of Agriculture also risked creating a famine by selling farmers only 30 percent of the fuel they needed for planting and harvesting. Later the government tried to curb inflation by requiring stores to file paperwork every time they raised a price. This meant that many store employees had to devote their time to filling out these government forms. Instead of curbing inflation this policy actually increased inflation because the stores tended to increase prices by larger increments so they would not have file forms for another price increase so soon.In October of 1993 they created a new currency unit. One new dinar was worth one million of the "old" dinars. In effect, the government simply removed six zeroes from the paper money. This, of course, did not stop the inflation. In November of 1993 the government postponed turning on the heat in the state apartment buildings in which most of the population lived. The residents reacted to this by using electrical space heaters which were inefficient and overloaded the electrical system. The government power company then had to order blackouts to conserve electricity.In a large psychiatric hospital 87 patients died in November of 1994. The hospital had no heat, there was no food or medicine and the patients were wandering around naked.Between October 1, 1993 and January 24, 1995 prices increased by 5 quadrillion percent. This number is a 5 with 15 zeroes after it. The social structure began to collapse. Thieves robbed hospitals and clinics of scarce pharmaceuticals and then sold them in front of the same places they robbed. The railway workers went on strike and closed down Yugoslavia's rail system. The government set the level of pensions. The pensions were to be paid at the post office but the government did not give the post offices enough funds to pay these pensions. The pensioners lined up in long lines outside the post office. When the post office ran out of state funds to pay the pensions the employees would pay the next pensioner in line whatever money they received when someone came in to mail a letter or package. With inflation being what it was, the value of the pension would decrease drastically if the pensioners went home and came back the next day. So they waited in line knowing that the value of their pension payment was decreasing with each minute they had to wait. Many Yugoslavian businesses refused to take the Yugoslavian currency, and the German Deutsche Mark effectively became the currency of Yugoslavia. But government organizations, government employees and pensioners still got paid in Yugoslavian dinars so there was still an active exchange in dinars. On November 12, 1993 the exchange rate was 1 DM = 1 million new dinars. Thirteen days later the exchange rate was 1 DM = 6.5 million new dinars and by the end of November it was 1 DM = 37 million new dinars. At the beginning of December the bus workers went on strike because their pay for two weeks was equivalent to only 4 DM when it cost a family of four 230 DM per month to live. By December 11th the exchange rate was 1 DM = 800 million and on December 15th it was 1 DM = 3.7 billion new dinars. The average daily rate of inflation was nearly 100 percent. When farmers selling in the free markets refused to sell food for Yugoslavian dinars the government closed down the free markets. On December 29 the exchange rate was 1 DM = 950 billion new dinars. About this time there occurred a tragic incident. As usual, pensioners were waiting in line. Someone passed by the line carrying bags of groceries from the free market. Two pensioners got so upset at their situation and the sight of someone else with groceries that they had heart attacks and died right there. At the end of December the exchange rate was 1 DM = 3 trillion dinars and on January 4, 1994 it was 1 DM = 6 trillion dinars. On January 6th the government declared that the German Deutsche was an official currency of Yugoslavia. About this time the government announced a NEW "new" Dinar which was equal to 1 billion of the old "new" dinars. This meant that the exchange rate was 1 DM = 6, 000 new new Dinars. By January 11 the exchange rate had reached a level of 1 DM = 80, 000 new new Dinars. On January 13th the rate was 1 DM = 700, 000 new new Dinars and six days later it was 1 DM = 10 million new new Dinars. The telephone bills for the government operated phone system were collected by the postmen. People postponed paying these bills as much as possible and inflation reduced their real value to next to nothing. One postman found that after trying to collect on 780 phone bills he got nothing so the next day he stayed home and paid all of the phone bills himself for the equivalent of a few American pennies.Here is another illustration of the irrationality of the government's policies: James Lyon, a journalist, made twenty hours of international telephone calls from Belgrade in December of 1993. The bill for these calls was 1000 new new dinars and it arrived on January 11th. At the exchange rate for January 11th of 1 DM = 150, 000 dinars it would have cost less than one German pfennig to pay the bill. But the bill was not due until January 17th and by that time the exchange rate reached 1 DM = 30 million dinars. Yet the free market value of those twenty hours of international telephone calls was about $5, 000. So despite being strapped for hard currency, the government gave James Lyon $5, 000 worth of phone calls essentially for nothing. It was against the law to refuse to accept personal checks. Some people wrote personal checks knowing that in the few days it took for the checks to clear, inflation would wipe out as much as 90 percent of the cost of covering those checks. On January 24, 1994 the government introduced the "super" Dinar equal to 10 million of the new new Dinars. The Yugoslav government's official position was that the hyperinflation occurred "because of the unjustly implemented sanctions against the Serbian people and state."

Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (Serbian Cyrillic: Петар II Петровић-Његош, 13 November 1813 – 31 October 1851), commonly referred to simply as Njegoš, was a Prince-Bishop (vladika) of Montenegro, poet and philosopher whose works are widely considered some of the most important in Montenegrin and Serbian literature.Njegoš was born in the village of Njeguši, near Montenegro's then-capital Cetinje. He was educated at several Montenegrin monasteries, and became the country's spiritual and political leader following the death of his uncle Petar I. After eliminating all initial domestic opposition to his rule, he concentrated on uniting Montenegro's tribes and establishing a centralized state. He introduced regular taxation, formed a personal guard and implemented a series of new laws to replace those composed by his predecessor many years earlier. His taxation policies proved extremely unpopular with the Montenegrin tribes, and were the cause of several revolts during his lifetime. Njegoš's reign was also defined by constant political and military struggle with the Ottoman Empire, and his attempts to expand Montenegro's territory while gaining unconditional recognition from the Sublime Porte. He was a proponent of uniting and liberating the Serb people, willing to concede his princely rights in exchange for a union with Serbia and his recognition as the religious leader of all Serbs (akin to a modern-day Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church). Although unification between the two states did not occur during his lifetime, Njegoš laid some of the foundations of Yugoslavism and introduced modern political concepts to Montenegro.Venerated as a poet and philosopher, Njegoš is well known for his epic poem Gorski vijenac (The Mountain Wreath), which is considered a masterpiece of Serb and South Slavic literature, and the national epic of Montenegro, Serbia, and Yugoslavia. Njegoš has remained influential in Montenegro and in neighbouring countries, and his works have influenced a number of disparate groups, including Serbian, Montenegrin and South Slav nationalists, as well as monarchists and communists.

FREE SHIPPING WORLDWIDE

IF YOU ARE SATISFIED WITH SERVICE, PLEASE LEAVE US A POSITIVE FEEDBACK

HAVE A GOOD LUCK!!!

The dinar was the currency of the three Yugoslav states: the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (formerly the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes), the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia between 1918 and 2003. The dinar was subdivided into 100 para (Cyrillic script: пара). In the early ...1990s, there was severe and prolonged hyperinflation due to a combination of economic mismanagement and criminality. Massive amounts of money were printed; coins became redundant; inflation rates reached the equivalent of 8.51×1029% per year. The highest denomination banknote was 500 billion dinars; it was worthless two weeks after it was printed. This hyperinflation caused five revaluations between 1990 and 1994; in total there were eight distinct dinari. Six of the eight have been given distinguishing names and separate ISO 4217 codes.Under Tito, Yugoslavia ran a budget deficit that was financed by printing money. This led to a rate of inflation of 15 to 25 percent per year. After Tito, the Communist Party pursued progressively more irrational economic policies. These policies and the breakup of Yugoslavia (Yugoslavia now consists of only Serbia and Montenegro) led to heavier reliance upon printing or otherwise creating money to finance the operation of the government and the socialist economy. This created the hyperinflation. By the early 1990s the government used up all of its own hard currency reserves and proceded to loot the hard currency savings of private citizens. It did this by imposing more and more difficult restrictions on private citizens' access to their hard currency savings in government banks. The government operated a network of stores at which goods were supposed to be available at artificially low prices. In practice these store seldom had anything to sell and goods were only available at free markets where the prices were far above the official prices that goods were supposed to sell at in government stores. All of the government gasoline stations eventually were closed and gasoline was available only from roadside dealers whose operation consisted of a car parked with a plastic can of gasoline sitting on the hood. The market price was the equivalent of $8 per gallon. Most car owners gave up driving and relied upon public transportation. But the Belgrade transit authority (GSP) did not have the funds necessary for keeping its fleet of 1200 buses operating. Instead it ran fewer than 500 buses. These buses were overcrowded and the ticket collectors could not get aboard to collect fares. Thus GSP could not collect fares even though it was desperately short of funds. Delivery trucks, ambulances, fire trucks and garbage trucks were also short of fuel. The government announced that gasoline would not be sold to farmers for fall harvests and planting. Despite the government's desperate printing of money it still did not have the funds to keep the infrastructure in operation. Pot holes developed in the streets, elevators stopped functioning, and construction projects were closed down. The unemployment rate exceeded 30 percent. The government tried to counter the inflation by imposing price controls. But when inflation continued, the government price controls made the price producers were getting so ridiculous low that they simply stopped producing. In October of 1993 the bakers stopped making bread and Belgrade was without bread for a week. The slaughter houses refused to sell meat to the state stores and this meant meat became unvailable for many sectors of the population. Other stores closed down for inventory rather than sell their goods at the government mandated prices. When farmers refused to sell to the government at the artificially low prices the government dictated, government irrationally used hard currency to buy food from foreign sources rather than remove the price controls. The Ministry of Agriculture also risked creating a famine by selling farmers only 30 percent of the fuel they needed for planting and harvesting. Later the government tried to curb inflation by requiring stores to file paperwork every time they raised a price. This meant that many store employees had to devote their time to filling out these government forms. Instead of curbing inflation this policy actually increased inflation because the stores tended to increase prices by larger increments so they would not have file forms for another price increase so soon.In October of 1993 they created a new currency unit. One new dinar was worth one million of the "old" dinars. In effect, the government simply removed six zeroes from the paper money. This, of course, did not stop the inflation. In November of 1993 the government postponed turning on the heat in the state apartment buildings in which most of the population lived. The residents reacted to this by using electrical space heaters which were inefficient and overloaded the electrical system. The government power company then had to order blackouts to conserve electricity.In a large psychiatric hospital 87 patients died in November of 1994. The hospital had no heat, there was no food or medicine and the patients were wandering around naked.Between October 1, 1993 and January 24, 1995 prices increased by 5 quadrillion percent. This number is a 5 with 15 zeroes after it. The social structure began to collapse. Thieves robbed hospitals and clinics of scarce pharmaceuticals and then sold them in front of the same places they robbed. The railway workers went on strike and closed down Yugoslavia's rail system. The government set the level of pensions. The pensions were to be paid at the post office but the government did not give the post offices enough funds to pay these pensions. The pensioners lined up in long lines outside the post office. When the post office ran out of state funds to pay the pensions the employees would pay the next pensioner in line whatever money they received when someone came in to mail a letter or package. With inflation being what it was, the value of the pension would decrease drastically if the pensioners went home and came back the next day. So they waited in line knowing that the value of their pension payment was decreasing with each minute they had to wait. Many Yugoslavian businesses refused to take the Yugoslavian currency, and the German Deutsche Mark effectively became the currency of Yugoslavia. But government organizations, government employees and pensioners still got paid in Yugoslavian dinars so there was still an active exchange in dinars. On November 12, 1993 the exchange rate was 1 DM = 1 million new dinars. Thirteen days later the exchange rate was 1 DM = 6.5 million new dinars and by the end of November it was 1 DM = 37 million new dinars. At the beginning of December the bus workers went on strike because their pay for two weeks was equivalent to only 4 DM when it cost a family of four 230 DM per month to live. By December 11th the exchange rate was 1 DM = 800 million and on December 15th it was 1 DM = 3.7 billion new dinars. The average daily rate of inflation was nearly 100 percent. When farmers selling in the free markets refused to sell food for Yugoslavian dinars the government closed down the free markets. On December 29 the exchange rate was 1 DM = 950 billion new dinars. About this time there occurred a tragic incident. As usual, pensioners were waiting in line. Someone passed by the line carrying bags of groceries from the free market. Two pensioners got so upset at their situation and the sight of someone else with groceries that they had heart attacks and died right there. At the end of December the exchange rate was 1 DM = 3 trillion dinars and on January 4, 1994 it was 1 DM = 6 trillion dinars. On January 6th the government declared that the German Deutsche was an official currency of Yugoslavia. About this time the government announced a NEW "new" Dinar which was equal to 1 billion of the old "new" dinars. This meant that the exchange rate was 1 DM = 6, 000 new new Dinars. By January 11 the exchange rate had reached a level of 1 DM = 80, 000 new new Dinars. On January 13th the rate was 1 DM = 700, 000 new new Dinars and six days later it was 1 DM = 10 million new new Dinars. The telephone bills for the government operated phone system were collected by the postmen. People postponed paying these bills as much as possible and inflation reduced their real value to next to nothing. One postman found that after trying to collect on 780 phone bills he got nothing so the next day he stayed home and paid all of the phone bills himself for the equivalent of a few American pennies.Here is another illustration of the irrationality of the government's policies: James Lyon, a journalist, made twenty hours of international telephone calls from Belgrade in December of 1993. The bill for these calls was 1000 new new dinars and it arrived on January 11th. At the exchange rate for January 11th of 1 DM = 150, 000 dinars it would have cost less than one German pfennig to pay the bill. But the bill was not due until January 17th and by that time the exchange rate reached 1 DM = 30 million dinars. Yet the free market value of those twenty hours of international telephone calls was about $5, 000. So despite being strapped for hard currency, the government gave James Lyon $5, 000 worth of phone calls essentially for nothing. It was against the law to refuse to accept personal checks. Some people wrote personal checks knowing that in the few days it took for the checks to clear, inflation would wipe out as much as 90 percent of the cost of covering those checks. On January 24, 1994 the government introduced the "super" Dinar equal to 10 million of the new new Dinars. The Yugoslav government's official position was that the hyperinflation occurred "because of the unjustly implemented sanctions against the Serbian people and state."

Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (Serbian Cyrillic: Петар II Петровић-Његош, 13 November 1813 – 31 October 1851), commonly referred to simply as Njegoš, was a Prince-Bishop (vladika) of Montenegro, poet and philosopher whose works are widely considered some of the most important in Montenegrin and Serbian literature.Njegoš was born in the village of Njeguši, near Montenegro's then-capital Cetinje. He was educated at several Montenegrin monasteries, and became the country's spiritual and political leader following the death of his uncle Petar I. After eliminating all initial domestic opposition to his rule, he concentrated on uniting Montenegro's tribes and establishing a centralized state. He introduced regular taxation, formed a personal guard and implemented a series of new laws to replace those composed by his predecessor many years earlier. His taxation policies proved extremely unpopular with the Montenegrin tribes, and were the cause of several revolts during his lifetime. Njegoš's reign was also defined by constant political and military struggle with the Ottoman Empire, and his attempts to expand Montenegro's territory while gaining unconditional recognition from the Sublime Porte. He was a proponent of uniting and liberating the Serb people, willing to concede his princely rights in exchange for a union with Serbia and his recognition as the religious leader of all Serbs (akin to a modern-day Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church). Although unification between the two states did not occur during his lifetime, Njegoš laid some of the foundations of Yugoslavism and introduced modern political concepts to Montenegro.Venerated as a poet and philosopher, Njegoš is well known for his epic poem Gorski vijenac (The Mountain Wreath), which is considered a masterpiece of Serb and South Slavic literature, and the national epic of Montenegro, Serbia, and Yugoslavia. Njegoš has remained influential in Montenegro and in neighbouring countries, and his works have influenced a number of disparate groups, including Serbian, Montenegrin and South Slav nationalists, as well as monarchists and communists.