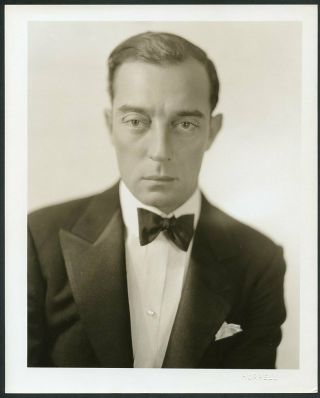

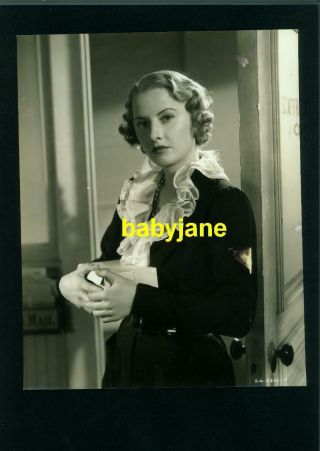

Sultry Beauty Carole Lombard Exquisite 1930s George Hurrell Photograph

Item History & Price

Noted for her energetic, often off-beat roles in... screwball comedies, Lombard was one of the highest paid stars of the late 1930s. Her career was cut tragically short when in 1942 she perished in an airplane crash on Mount Potosi, Nevada while returning from a war bond tour.

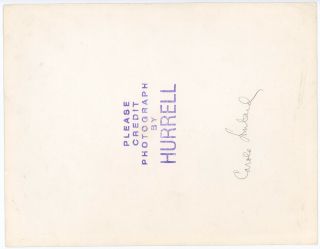

Photograph measures 10.25" x 8" on a glossy, single weight paper stock with the photographer's ink stamp on verso.

Guaranteed to be 100% vintage and original from Grapefruit Moon Gallery.

More about Carole Lombard:

It was a testament to Carole Lombard's remarkably unique talents that her star shone brightest during some of the darkest days in U.S. history. Throughout the 1930s, while millions of Americans struggled to survive under the crushing weight of the Great Depression, Lombard reigned as Hollywood's premier comedic actress – anointed by LIFE magazine as "America's Screwball Queen." Elegant but accessible, beautiful but unpretentious, Lombard was a study in contrasts who nevertheless fostered a strong sense of identification with her audience who knew her every quirk both on- and off-screen. Her fans recognized in her a small-town girl who had made good, and their embrace of her bordered on the worshipful. Lombard's celebrated union to Clark Gable, the "King of Hollywood, " only cemented her status as a beloved icon in her own time and one-half of the most fabled coupling in Tinseltown history. In comedy classics like "Twentieth Century" (1934), "My Man Godfrey" (1936), and "Nothing Sacred" (1937), she stole every scene she was in, ensuring her place in film history. Sadly, it was a history cut short when, after selling war bonds for a country recently attacked at Pearl Harbor, the patriotic actress died in an airplane crash in 1942, leaving behind a devastated nation and even more devastated husband. For fans, her posthumously released final film, the brilliant and timeless Ernst Lubitsch Nazi satire "To Be or Not to Be" (1942) was her final gift to the world, containing perhaps her best performance in a career unlike any other.

Carole Lombard was born Jane Alice Peters in Fort Wayne, IN, on Oct. 6, 1908. She was the youngest of three children and, although petite and pretty, loved competing with her two older brothers, Frederick and Stuart, in a variety of sports. A tomboy adored by her family and friends, she enjoyed a happy, stable childhood until her parents suddenly separated in 1914. Bessie, Lombard's mother and best friend, packed up her kids and moved them to Los Angeles, harboring hopes that her daughter might someday break into the burgeoning film industry. In a stroke of good luck straight out of a "picture show, " silent film director Allan Dwan spotted Lombard playing baseball in the street with some neighborhood kids. Taken aback by her exuberance, he cast her in the silent film "A Perfect Crime" (1921). The part was small; the movie forgettable, but for the 12-year-old beauty, none of that mattered. Bessie and Lombard resolved together that she would someday become a movie star.

While she was still in junior high and high school, Lombard took acting and dancing lessons, briefly toured with a theater troupe, and auditioned tirelessly for movie roles. She was driven to succeed, but not at the expense of leading a normal life. She stayed close to her mother and brothers and attracted a large circle of friends at Los Angeles' Fairfax High School where - ever the tomboy - she was a star on the track team. She managed to appear in small parts in a few low-budget films, but nothing notable until she caught another break. An executive from Fox Pictures (soon to merge with Twentieth Century Productions) saw her dancing the Charleston at the famed Coconut Grove nightclub and asked her to take a screen test. Fox soon signed the pretty ingénue to a contract, giving her the screen name "Carol Lombard" - she would later add the extra "e" to her first name for "good luck" - and putting her to work.

Lombard started out acting in cheapie Westerns like "Hearts and Spurs" (1925) and "Durand of the Bad Lands" (1925). The material may have been mediocre, but Lombard was not. It was clear to audiences and movie executives that she possessed that ineffable "It" quality. Then, just as her career was taking off, she suffered a massive setback. Injured in a car crash - her face went into the windshield - she required major plastic surgery to repair a large scar on the left side of her face. Knowing the results would be best without it, she went under the knife sans anesthetic. Thankfully, the surgery was largely successful; the scar was only slightly visible and Lombard would later learn how to appropriately light her face to cover up this single flaw. But this being the Silent Era, when close-ups of actors' faces did the work of dialogue, Lombard was terrified her career was over. Ironically, it was just about to take off and her scar would help shape her later on-screen identity.

Mack Sennett, the pioneer producer of slapstick comedies, knew a good thing when he saw it and snatched up Lombard to appear in his low-budget two-reelers. He reasoned nobody would notice Lombard's scar when she was slipping on banana peels and getting pies thrown in her face. She cut her teeth on Sennett's signature brand of physical comedy, using silent vehicles like "The Campus Vamp" (1928) and "Matchmaking Mamma" (1929) to hone the comic timing that would make her a star when sound arrived. Whereas many actors with less than desirable accents lost their livelihoods with the advent of talkies, Lombard had a pleasant, engaging voice. She segued into speaking roles easily with the drama "High Voltage" (1929) and never looked back.

Paramount Pictures signed Lombard to a contract in 1930, initiating her ascension to the pinnacle of Hollywood actresses. However, the studio initially had no idea how to cast their latest blonde beauty. That same year, she met the actor William Powell. Although he was 16 years her senior, they fell in love and were married in 1931. Powell saw in Lombard what audiences did not quite see yet onscreen: she was genuine, kind, funny. She did hold a powerful attraction for men because she could be elegant and kooky, gorgeous and grounded; a lover and a pal all at the same time with the best cheekbones this side of Marlene Dietrich. Unfortunately, these qualities were not enough to save the marriage. Lombard, an extrovert, and Powell, an introvert, divorced in 1933. The divorce was not bitter, however, and they remained friends for the rest of her life. In fact, it would be Powell who campaigned for his ex to land the role that would make her a major star.

Ever cast as a worldly but humorless vixen, Lombard worked steadily throughout the early 1930s in an assortment of films. One of the most notable was the romantic drama "No Man of Her Own" (1932) - not because the movie was particularly good, but because she starred opposite Clark Gable. The two had met at a party in 1931 while they were both married to other people, but the spark of attraction played out only on film at that time. In fact, Lombard found Gable a bit of a stuffed shirt, and so thus, during the film's wrap party, presented her co-star with a ham covered with his photo. Lombard had little interest in Gable for other reasons. She had begun a passionate romance with Italian crooner Russ Columbo, who was devoted to her. However, the couple's happiness was cut tragically short when the up-and-coming singer was killed by a freak gun accident at his friend's home. Apparently, an antique gun still contained powder inside and shot a lead ball into Columbo's forehead after being set off by a cigarette lit against the wooden stock. He died instantly. Not surprisingly, Lombard was inconsolable, but focused on work even more than before.

While Lombard was a well-liked actress - particularly within the industry more than amongst general movieg rs - it took her role opposite the great John Barrymore in "Twentieth Century" to catapult her out of the peroxide blonde brigade and to the next level. A hilarious film which - along with "It Happened One Night" (1934) - ignited the screwball comedy genre of the 1930s, the movie was a critical and commercial smash and, at long last, showcased Lombard's comedy skills to great effect. Starring as the divaesque stage actress, Lily Garland, to Barrymore's tyrannical producer/svengali, Oscar Jaffe, Lombard drew tear-induced laughter with her over-the-top antics - holding her own against the great Barrymore, who would later say that she was the "greatest actress I have ever worked with, bar none."

Recognized now as a top comedienne, the savvy Lombard demanded top dollar for her services. Despite her newfound fame and wealth, she held on to her unpretentious personality, refusing to lounge in her on-set dressing trailer; preferring instead to hang on set with the prop men and extras between takes. She was famous for sticking up for her crew, often refusing to take a role if her favorite cameraman or grip was not hired. One of the first feminists in the business, she became very selective about roles, standing up to the male-dominated studio system - out-cussing even the crudest of studio heads. It was for her profanity-laced manner of speaking, that amongst friends and co-workers, she was lovingly referred to as "the profane angel" - because she looked like an angel but swore like a longshoreman. Adding to the effusive joy she provoked, she was a slavish practical joker, with many of her stunts entering Hollywood lore - from showing up to a "nervous breakdown" party in an ambulance to corralling three cows festooned with nametags on set for Alfred Hitchcock, who had famously remarked that all actors "were cattle." She was, in fact, impossible not to like, and everyone from the studio heads down to the studio security guards fell in love with her.

Lombard's choosiness could be seen in the relatively meager number of films she made after her breakout in "Twentieth Century." "Hands Across the Table" (1935) and "The Princess Comes Across" (1936) were serviceable romantic comedies co-starring her new on-screen partner, Fred MacMurray, but "My Man Godfrey" re-wrote the rules of screwball forever and made Lombard its queen. Starring opposite ex-husband William Powell - who would not take the role unless his ex was given the lead opposite him - Lombard earned an Oscar nomination playing the ditzy heiress Irene Bullock. The crazy premise - that a scatterbrained socialite would go to the city dump to hire a butler (Powell) who she later falls in love with - tapped into Depression America's powerful impulse for escapism and redemption. Unlike nearly all of her peers, Lombard barely seemed to be acting; her unforced glamour and naturalism were pitch perfect and it was for this role that she was nominated for her first and only Best Actress Oscar. She would lose out to Luise Rainer for "The Great Ziegfeld."

After "Godfrey, " Lombard was at the peak of her powers personally and professionally, starring again with MacMurray in two back-to-back 1937 hits, "Swing High, Swing Low" and "True Confession." She also did outstanding work in another screwball comedy, "Nothing Sacred" - her only Technicolor film and one of the greatest films of the genre. Playing a woman who exploits a reporter's cynical interest in her alleged radium poisoning, Lombard again turned the ridiculous into the sublime, and her fisticuffs with co-star Frederic March was heralded as the funniest scene of the year. Due in part to her popularity, but more in part to her business savvy, Lombard ended the year as the highest paid actress in Hollywood, earning a reported $500, 000 a year. She earned the respect of President Franklin D. Roosevelt for publicly declaring she was more than happy to see a huge chunk of it go to taxes.

While enjoying her star status, as well as a reputation as the town's best event planner - her wacky parties would still be discussed years after her death - Lombard was also finding romance again. Two years after Columbo's accidental death, Lombard met up with Gable at a 1936 party she was hosting. Times being different, they immediately fell for one another and began dating on the sly, as Gable was married at the time. Because the couple was so adored both apart and together, fans accepted them without question - a rarity at a very prudish time when Lombard would have otherwise been labeled a harlot. In fact, Rhea Gable became the villain of the mix, with fans urging her to divorce the King so he could freely be with Lombard. A hesitant Gable eventually agreed to play Rhett Butler in "Gone with the Wind" (1939) for the sole purpose of earning a big enough paycheck to finally pay off his ex-wife. The glamorous twosome - who affectionately called each other "Ma" and "Pa" - finally tied the knot after three years of dating on March 29, 1939, delighting fans and cementing their status as one of the most revered of Hollywood couples.

By this point, Lombard was so beloved by audiences, it seemed she could do no wrong. Despite a rare misstep with the seriously unfunny comedy "Fools for Scandal" (1938), she shifted gears to show her dramatic range, lending her elegant ebullience to middling tearjerkers like "Made for Each Other" (1939), "They Knew What They Wanted" (1940) and "Vigil in the Night" (1940). Audiences were less than enthused by their wacky girl going straight, so Lombard signed on for Alfred Hitchcock's only comedy, "Mr. and Mrs. Smith" (1941). Reportedly, Hitch took on the project solely to work with Lombard, as he knew comedy was not his forte. A good time was had by all during the shoot - Lombard directed Hitchcock's notorious cameo, making the flustered director re-do the simple scene over and over, much to the amusement of the crew. The comic again returned to her roots by taking the lead opposite Jack Benny in Ernst Lubitsch biting Nazi satire, "To Be or Not To Be" (1942), starring as Maria Tura, member of a Polish acting troupe which becomes embroiled in a Polish soldier's attempts to track down a German spy. In the film, Lombard was radiant as the cheating wife of blowhard actor Joseph Tura (Benny), who uses her considerable charm to seduce a variety of men, all under the distrustful eye of her frustrated husband.

On the homefront, the Gables were enjoying wedded bliss. Gable - who had lost his mother during childbirth - seemed to blossom in the relationship, having married much older women previously. In Lombard, he had more than met his match. Not only did she go out of her way to make him laugh, but she took up many of his interests without losing herself in the process. The same woman who rented out the entire Santa Monica Pier for one of the most famous bashes in the history of the town, was now perfectly content to hole up with her husband in muddied duck blinds in South Dakota. In fact, Lombard eventually became a better shot than her spouse, a life-long hunter. She set up house on a ranch in Encino, CA, creating a rugged and masculine home for the man who had never really had one. When not off on hunting trips, they spent their downtime riding horses, raising chickens and entertaining a few close friends. The only sore spot continued to be his sometimes wandering eye and their inability to conceive a child. Unfortunately, a dramatic event was about to intervene on their domestic tranquility.

After the Dec. 7, 1941 attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor, America was plunged into WWII. When America entered the war, Gable assumed the chairmanship of the Hollywood Victory Committee, and because he himself was not enthused by the idea, nominated his wife to travel the country for one of the first war bond drives. Ever the patriot, she plunged into planning a trip which would culminate in her home state of Indiana. After selling more war bonds in a single day than anyone - $2 million - she, her mother, and Gable's MGM press agent Otto Winkler (along to chaperone) flipped a coin on whether to return to California via train or plane. Bessie was petrified of flying, so pled with her daughter to take the train. Lombard would have none of it, due mainly to a sneaking suspicion that Gable might be carousing with his latest co-star, Lana Turner, on the set of their film "Somewhere I'll Find You" (1942). Lombard won the coin toss. The trio boarded a DC-3 and started the long journey home from Indianapolis. Despite being asked to disembark to make room for soldiers during one of the plane's stops, Lombard - who was technically on a government mission - for once in her life pulled rank, insisting she and the others remain on the plane.

At the same time that Gable and a group of friends awaited the star with a welcome home party, the plane crashed shortly after take-off on Jan. 16, 1942. Flying in a blackout zone, the pilot was off course and with less than 100 feet making the difference, collided with the top of Table Rock Mountain just southwest of Las Vegas, NV. Lombard, her mother, Winkler and 18 other people died instantly. Gable, grief stricken and inconsolable, traveled to Las Vegas to claim her body; even attempting to climb the snow-laden mountain along with the vast army of volunteers. Close friends like MGM publicity man Howard Strickling and actor Spencer Tracy - petrified of what might be up there - insisted Gable stay behind. Thankfully Gable was spared the sight of his wife's badly burned and decapitated body. All that was found to identify the once vibrant star were a pair of melted diamond and ruby brooches from Gable. She was 33 years old.

As per her directions, Lombard was interred at Glendale's Forest Lawn Cemetery, following a small, quiet ceremony unbefitting a woman as universally loved as she. Unsure how audiences would receive a comedy starring the late actress, United Artists released "To Be or Not to Be" in tribute to Lombard. Receiving some of the best reviews of her career, the film became yet another classic in her canon, earning even more respect by historians years later for its biting commentary on the Nazi regime and war in general. President Roosevelt publicly eulogized Lombard, famously saying " she is and always will be a star, one that we shall never forget, nor cease to be grateful to." He would also posthumously award her the Medal of Freedom for being the first woman killed in the line of duty in WWII. Two years after her death, a liberty ship was christened the U.S.S. Carole Lombard. The mountain the plane had failed to clear became Carole Lombard Mountain. The Hollywood community continued to mourn her on a personal level - Lucille Ball often made career decisions based on Lombard appearing to her in dreams. And on screen, no one was ever quite able to capture the essence of beautiful and funny as deftly as Lombard did, with blonde comediennes through the years earning "Lombard-like" comparisons, including Cameron Diaz and Tea Leoni. But no one really came close.

And as for Gable - he would never recover from his loss, feeling deep-seated guilt over her rush home. At the age of 41, he volunteered for service, as well as for the most suicidal bombing missions over Germany. Following his return home from the war, Lombard's bedroom remained untouched for years, until the increasingly alcoholic actor remarried twice - both to women who resembled older versions of his dead wife and both of whom referred to him as "Pa." Upon his sudden death by heart attack in 1960, Gable's dying wish was to be laid to rest next to Lombard, despite being married at the time to Kay Spreckles. She granted his final request and Hollywood's greatest and most tragic love story played out its final scene.

TCM | Turner Classic Movies Biography By Jenna Girard

More about George Hurrell:

Recognized for his gorgeously lit, glamorous images of movie icons, photographer George Hurrell is considered one of the masters of Hollywood’s still portrait photography. An innovator as well as craftsman, Hurrell moved between studios, his independent galleries, and fashion work as the mood hit him. In fact, he could be said to suffer from attention deficit disorder, as he couldn’t sit still, and when bored, moved on to newer pastures. He remained active for decades, and his work attracts high demand, selling for high prices.

Born in Cincinnati, Ohio June 1, 1904, to a large English/Irish family, George Hurrell served as an altar boy while spending his free time drawing and studying art as a boy. While in high school, he signed up with the Quigley Seminary in Chicago to study for the priesthood, but girls and art drew him to art school instead. Short attention spans and being bored caused him to move from studying at the Chicago Art Institute to the Academy of Fine Arts and back.

In 1923, portrait photographer Eugene Hutchinson hired him as a gofer and assistant. Hurrell studied the art of photography, gaining more opportunities in the studio such as developing negatives. With extra money, he bought a used camera and began shooting studies of his own, as well as shooting artwork for artists and also continuing to paint. Landscape painter Edgar Alwyn Payne visited the Art Institute in 1925 to lecture, and viewed some of Hurrell’s artwork afterwards. He suggested Hurrell accompany him to Laguna Beach, California if he really wanted to paint, and Hurrell signed on. They arrived in the beach town on June 1, 1925, Hurrell’s birthday. Hurrell moved into director Mal St. Clair’s small bungalow, painted, explored the countryside, and began experimenting with his camera in his free time.

To earn some extra money, he made photos of artists’ paintings, and began taking portraits of artists. In late 1925, he met Florence “Pancho” Barnes at a Laguna party, and they quickly became friends. She sent Pasadena socialites his way for elegant portrait photographs. In 1926, Hurrell made photos of Payne’s work for a monograph that served as a catalog of Payne’s work for a 1926 Stendhal Gallery exhibit in Los Angeles. Little by little, photography was becoming his life. To facilitate his increasing shooting of portraits, Hurrell moved to 672 S. Lafayette Park Place, studio 9, in 1927. In 1928, he printed negatives for a visiting Edward Steichen, learning how much money a successful photographer could charge clients. He was gaining an unique style, a lush almost halo effect around his subjects. This look was achieved because he had inferior equipment that didn’t quite focus, and he also greatly retouched his negatives. Retouching would become an essential part of his look.

His friend Barnes brought along her friend, actor Ramon Novarro, in 1929. He needed elegant portraits to try and help promote a hoped for operatic tour of Europe. Hurrell shot elegant, soft focus shots of him that suggested Roman art. These photos would appear later that year in the rotogravure section of The Los Angeles Times, with the first credit, “Photo by Hurrell.” Novarro happened to show them to his friend and fellow actor Norma Shearer, who found them fascinating. She needed a hook to grab the part of a sexy vamp in the film “The Divorcee, ” so hired Hurrell for a special shoot. After difficulties in getting the proper mood, Hurrell’s clowning broke a camera and caused her to laugh, setting the stage for a successful shoot. These sensual images of her caused her husband Irving Thalberg to cast her in the role, for which she won an Academy Award. The glowing shots also earned him a job at MGM after photographer Ruth Harriet Louise left.

When Hurrell replaced Louise, he kept her assistant Al St. Hilaire to assist him and worked in the smaller of two studios on the lot; Clarence Sinclair Bull as head of the department worked in the largest. Hurrell followed his own rules, thanks to the support of Norma Shearer. While taking photos, the artist danced, goofed off, and played music, helping himself and the stars relax. Hurrell’s job was to create stunning portraits of MGM stars to run in magazines and newspapers. He shot “in-character” portraits a day after films wrapped, per Mark Vieira in his excellent book “George Hurrell’s Hollywood.” Still photographers shot like crazy on the MGM lot in 1930-1931; Vieira reports that 25, 000 negatives and 14, 000 prints a week were developed, making it a virtual shooting factory.

Hurrell created his unique look with retouching that took three hours per negative, but MGM tried to speed the process along with a retouch artist team, none of whom knew or understood Hurrell’s own unique technique. The studio and the photographer reached a compromise enabling him to hire an assistant, Andrew Korf, to retouch the negatives. Hurrell also achieved his elegant style by employing multiple lights and lenses along with having actors wear no makeup, enhanced by his deft retouching.

The photographer’s retouching technique featured several steps. He applied powdered graphite to the emulsion of the negative, then rubbed it in patterns with a rolled up paper called a blending stump. This embellished facial highlights. In the dark room, he used the printing techniques known as “burning” to increase tonal range and to make less important areas go dark and recede, per Vieira in his excellent book. One actor went even farther to improve the look of his skin; Johnny Weissmuller applied baby oil to enhance highlights, inspiring Hurrell.

To prevent boredom as well as to continue honing his skills, Hurrell began taking freelance portrait shots of other studios’ stars on the weekend. He also tended to process the photos on the MGM lot. Studio executives discovered this and the photographer quit in 1932 before they could fire him. He opened his own studio at 8706 Sunset Blvd., taking photos of stars from virtually all the lots, even MGM’s, as well as fashion shoots. Joan Crawford, his favorite model, continued using him, as they enjoyed each other’s company. She stated. “He worked to catch you off guard.” He’d shoot while the two were talking or laughing.

Hurrell began traveling to the East Coast to shoot for magazines and advertising firms, as well as entering camera shows, winning awards several years in the United States Camera Salon held in New York, per the New York Times. In 1937 he was one of the judges, along with such photographers as Arnold Genthe, Edward Steichen, Paul Outerbridge, and Will Connell, per the October 7, 1937, New York Times. Los Angeles galleries exhibited his work as well. Publications such as “Esquire” and “Vogue” featured his photographs. “Esquire” even called him the Rolls-Royce of motion picture still photographers.

In 1938, Warner Bros. hired him as portrait photographer, and Hurrell would “…devote his entire time to photographic exploitation of Warners personalities, ” per the July 25, 1938, Daily Variety. While at the studio, he added “oomph” to Ann Sheridan, as well as supposedly appearing as himself in the film “Models” in 1939 with the actress. In 1940, the studio appointed him along with 11 others such as costumer Orry Kelly, makeup man Perc Westmore, cinematographer Ernest Haller, director Anatole Litvak, to select two women contract players to groom for stardom, which the studio hoped to turn into an annual event.

Hurrell left the studio in 1940 to return to private practice, shooting for magazines in New York. In 1941, Howard Hughes paid him $4000 to glamorize Jane Russell for the film “The Outlaw, ” which would sit on the shelf for years because of censorship problems. It was Hurrell who suggested a shoot in a haystack. One of these sessions was recorded for posterity by photographer G. T. Allen of “U. S. Camera” magazine. Soon after, Hurrell set up a large studio at 333 N. Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills. He surprisingly discovered after renting the space that actress Greta Garbo was his landlord.

The photographer soon headed to Columbia in July 1942 as a special photographic portraitist, replacing the departing A. L. Whitey Schafer. Hurrell only lasted a short time however, before applying to the Army Signal Corps. in October, per Daily Variety. While in the Army, he shot portraits for the Pentagon, but signed out in 1943, returning to Hollywood. In 1944, Hurrell supposedly appeared in the film “The Hairy Ape” as a photographer.

Hurrell decided to enter the television business in 1947, producing, hosting, and starring in a reality show “Camera Highlights” on the DuMont’s showcase time on WABD, it’s New York station. According to Variety, many camera and manufacturing companies were eager to showcase their products in the show and to act as sponsors. Hurrell would teach real amateur photographers how to improve their work after viewing samples. Unfortunately, the trade panned the show in its June 25, 1947, edition, stating, “Here’s another good television idea gone wrong through insufficient preparation, poor scripting and faulty direction.” The paper thought the adlibbing atrocious, but felt that “Hurrell demonstrated a pleasant enough video personality to hold down a weekly show, given enough time to memorize his lines.” The show failed.

The artist returned to the West Coast, and in 1950 he formed Hurrell Productions with Roy O. Disney, Gunther Lessing, and Paul Pease, to make live action and animated features and TV films, shooting on the Disney lot, per the December 13, 1950, Daily Variety. Several years before, Hurrell had married Walt Disney’s niece, which aided him in setting up the deal. The company existed for several years, but mostly focused on commercial work. He returned to East Coast fashion shoots.

Hurrell headed the Twentieth Century-Fox Studios portrait department, shooting for TV shows and films like “Star!” and “Bang Bang”in the 1960s. The difficult stars and cheaper conditions both angered and saddened him. He complained to the Los Angeles Times on June 1, 1969 that “Working on a movie now is like being a combat photographer.” Stars now refused to pose, arrived late, or acted up, not like in the golden era. As he stated, “In the old days when a star was asked to pose for a publicity still, they posed and no nonsense.”

His work was also featured in major camera shows at places like the Museum of Modern Art in 1965 along with works of photographers like Cecil Beaton, Julia Margaret Cameron, Irving Penn, Edward Steichen, Man Ray and Richard Avedon. Hurrell’s portraits also appeared in Los Angeles exhibits. The photographic world now considered him a master as well.

Hurrell released his book “The Hurrell Style” in 1976 with text by Whitney Stine, featuring stories and commentaries from the photographer. He began making appearances talking about his work, and his photographs appeared in many exhibitions. A documentary about his life and career called “Legends in Light” was released in 1995 after his death, but “Variety” felt it revealed little of the man himself. The review did point out that the show revealed his still energetic and enthusiastic personality at the age of 87.

Biography From: Mary Mallory: Hollywood Heights – George Hurrell