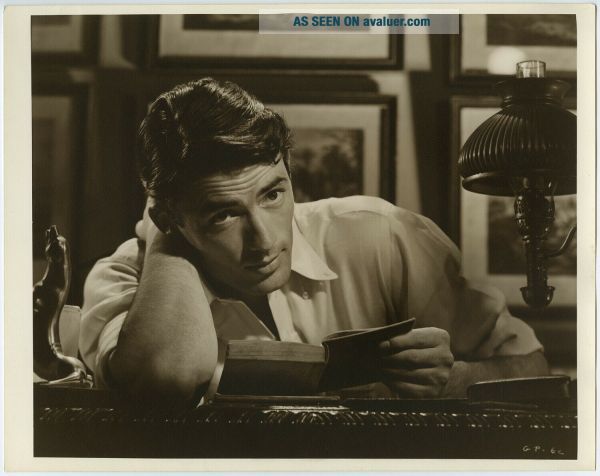

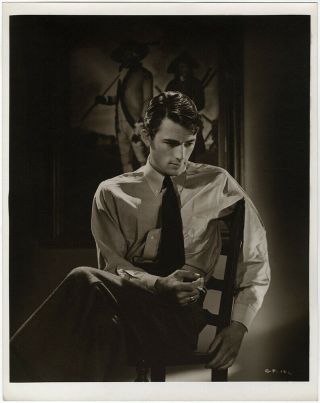

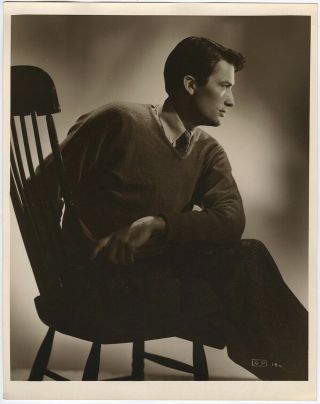

Moody 1940s Ernest A. Bachrach Gregory Peck Large Dramatic Photograph

Item History & Price

One of the most popular film stars from th...e 1940s to the 1960s, Peck received five Academy Award for Best Actor nominations, and won once – for his performance as Atticus Finch in the 1962 drama film To Kill a Mockingbird. U.S. President Lyndon Johnson honored Peck with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969 for his lifetime humanitarian efforts. In 1999, the American Film Institute named Peck among Greatest Male Stars of Classic Hollywood cinema, ranking him at No. 12.

Photograph measures 14" x 11" on a matte double weight paper stock.

Guaranteed to be 100% vintage and original from Grapefruit Moon Gallery.

More about Gregory Peck:

As an actor who conveyed moral certitude and unwavering strength, Gregory Peck became the unofficial conscience of postwar Hollywood, turning in several iconic performances in some of cinema's most important films. Peck began appearing in movies during the war with "Days of Glory" (1944) and became an almost instant star thanks to his Oscar-nominated performance in "The Keys of the Kingdom" (1945). He went on to portray an amnesiac psychoanalyst in Alfred Hitchcock's "Spellbound" (1945), turned in another Academy Award-worthy performance in 'The Yearling" (1946) and played against type in "Duel in the Sun" (1946). Following seminal work in "Twelve O'Clock High" (1949), "Roman Holiday" (1953) and "Moby Dick" (1956), Peck took on the role that became inextricably tied to his career, that of Atticus Finch in "To Kill a Mockingbird" (1962), which earned him his only Oscar for Best Actor while inspiring audiences for generations. He had a major box office hit with "The Guns of Navarone" (1961), starred in the original "Cape Fear" (1962) and reunited with "Mockingbird" director Robert Mulligan for "The Stalking Moon" (1969). His career began to slow in the 1970s, though he was notable in "The Omen" (1976) and "The Boys of Brazil" (1978). Following a turn as Abraham Lincoln in "The Blue and the Grey" (CBS, 1982) and his Emmy-nominated performance in a contemporary remake of "Moby Dick" (USA, 1998), Peck left behind a legacy as an iconic performer who exerted creative independence while becoming a beloved actor to generations fans.

Born on April 5, 1916 in La Jolla, CA, Peck was raised in a Catholic home by his father, Gregory, a druggist, and his mother, Bernice. When he was six years old, his parents divorced and he went to live with his maternal grandmother in Los Angeles, where he attended the St. John's Military Academy. But his grandmother soon died and his father resumed parenting duties, bringing his son back down to San Diego, where he graduated from San Diego High School. He spent a year studying at San Diego State College before transferring to the University of California at Berkeley, where he studied language and medicine, was a member of the rowing team and became interested in acting after a trip to New York City, where he was inspired by a Broadway production of "I Married an Angel" (1928). Upon his return to Berkeley, Peck withdrew from studying medicine and joined a small theater group on campus. He graduated in 1939 and made his way back to New York, where he attended the Playhouse School of Dramatics - later changed to the Neighborhood Playhouse - under a two-year scholarship, studying under Rita Morgenthau, Irene Lewisohn, Sanford Meisner and Martha Graham.

Peck's first couple of years in New York were nothing short of a struggle. Often broke, he worked as a barker at a concession stand for the 1939 World's Fair and a tour guide at Radio City Music Hall, though sometimes he lived hand-to-mouth and even slept in Central Park. Two years after his arrival, Peck made his professional stage debut with a small role in the touring company of "The Doctor's Dilemma" (1941), starring Katharine Cornell, and soon made his Broadway bow in "Morning Star" (1942). Peck's excellent notices were enough to attract the attention of Hollywood talent scouts. He would go on to sign contracts with RKO, 20th Century Fox, Selznick Productions and MGM. Because of a spinal injury suffered in dance class - not while rowing, as was commonly believed - Peck was exempt from service during World War II, which allowed the actor to fill in the void left behind by a scarcity of leading men. His first film, "Days of Glory" (1944), an over-ripe tribute to Russian peasant resistance against the Nazis, featured Peck as a strong-boned resistance leader. But it was "The Keys of the Kingdom" (1945) - in which he was a dedicated Roman Catholic missionary to China - that made him a star. It was the first of his incarnations as an authority figure of quiet dignity and uncompromising single-mindedness, and also the first of five Academy Award nominations for Best Actor.

Peck capitalized on his newfound star power and starred opposite Ingrid Bergman in Alfred Hitchcock's psychological suspense thriller, "Spellbound" (1945), in which he played a psychiatrist and troubled amnesiac who may have committed murder. He next played a warm and loving father in "The Yearling" (1946), earning another Oscar nod for Best Actor, while he was the complete opposite as a no-good, womanizing villain who seduces Jennifer Jones in King Vidor's "Duel in the Sun" (1946). After the unsuccessful adaptation of Ernest Hemingway's popular short story, "The Macomber Affair" (1947), Peck was a British barrister taking on the case of a woman (Alida Valli) accused of murdering her wealthy husband in Alfred Hitchcock's minor work, "The Paradine Case" (1947). Meanwhile, he garnered his third Oscar nomination for Best Actor as a writer who pretends to be Jewish to expose anti-Semitism in Elia Kazan's powerful drama "Gentleman's Agreement" (1947). Turning back to the Western with "Yellow Sky" (1948), he was the head of an outlaw gang who takes refuge in a frontier ghost town and butts heads with one of the lone inhabitants (Anne Baxter).

Peck earned a fourth Academy Award nomination for Best Actor for his sterling performance in the World War II drama, "Twelve O'Clock High" (1949), in which he played a hard-driving brigadier general who sees the futility of boosting his men's morale as they prepare to be sent to their deaths on a dangerous bombing mission. In "The Gunfighter" (1950), Peck was an aging gunslinger who is sick of killing, but is forced into confrontation by a young outlaw - a role originally intended for John Wayne. Following leading turns in the biblical drama "David and Bathsheba" (1951) and the adaptation of Hemingway's "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" (1952), Peck showed his more lighthearted side with the romantic comedy "Roman Holiday" (1953), starring opposite Audrey Hepburn as an expatriate reporter from America who falls for her Princess Anne. Though Peck's contract stipulated that he receive solo top billing opposite the then-relatively unknown Hepburn, he suggested midway through shooting to director William Wyler that she should indeed receive equal billing - an unheard of gesture that demonstrated the actor's genuine nature. He next played a Canadian pilot trapped in Burma surrounded by the Japanese World War II drama "The Purple Plain" (1954) and was an ex-arm officer trying to be a television writer after the war in "The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit" (1956).

Peck next delivered one of his most indelible performances, channeling his maniacal obsession as Captain Ahab, who relentlessly pursues the great white whale in John Ford's adaptation of Herman Melville's "Moby Dick" (1956). Peck enjoyed a successful producing career beginning with William Wyler's "The Big Country" (1958), a Western in which he starred as an ex-sea captain forced to take sides in battle against Burl Ives and sons over water rights. He followed with "Pork Chop Hill" (1959), an uncompromising war film that was almost documentary-like in its story of men dying for a worthless hill in the Korean War. He also appeared in Stanley Kramer's "On the Beach" (1959), which contained a strong message that mankind could destroy the Earth through nuclear war. Meanwhile, he made the first of four collaborations with director J. Lee Thompson on the classic war film, "The Guns of Navarone" (1961), in which he was part of an Allied force tasked with taking out a set of huge Nazi cannons that are well-placed and hard-to-reach on an Aegean island. The film was a major box office success and the top grossing film of that year.

The following year, Peck delivered his most iconic performances, portraying morally courageous small-town lawyer, Atticus Finch, in "To Kill a Mockingbird" (1962), a role that not only earned him his only Academy Award for Best Actor, but was considered by many as the one he was born to play. In fact, his own persona off screen was not unlike the character he played on screen, and Peck considered himself lucky to have managed to play such a beloved role. Also that year, he was an attorney whose family is stalked by a criminal (Robert Mitchum) he sent to jail in the original "Cape Fear" (1962), and joined an all-star cast that included Henry Fonda, Karl Malden, Debbie Reynolds, John Wayne and Jimmy Stewart for the epic Western "How the West Was Won" (1962). He next battled stodgy bureaucracy and macho military mentality as an army psychiatrist in "Captain Newman, M.D." (1963), playing an aging Catalan guerilla in "Behold a Pale Horse" (1964) and an unconscious amnesiac trying to piece together his forgotten life in the Hitchcockian thriller "Mirage" (1965).

After narrating the memorial tribute documentary "John F. Kennedy: Years of Lightning, Day of Drums" (1966), Peck starred opposite Sophia Loren in the political thriller "Arabesque" (1966), before reteaming with "Mockingbird" director Robert Mulligan for the Western "The Stalking Moon" (1969). He next reunited with Thompson for "Mackenna's Gold" (1969) and "The Chairman" (1969), and was a small town sheriff who develops a relationship with a local girl (Tuesday Weld) in John Frankenheimer's "I Walk the Line" (1970). In 1971, Peck received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Screen Actors Guild, and that year played a prisoner falsely imprisoned for a bank robbery seeking revenge on the man who set him up in Henry Hathaway's Western "Shoot Out" (1971). Following two features he produced but in which he did not act, "The Trial of the Catonsville Nine" (1972) and The Dove" (1974), Peck returned to the screen for "The Omen" (1976), playing a U.S. ambassador who inadvertently replaces his dead newborn son with the spawn of the devil. He followed up by playing two diametrically opposed historical characters, portraying World War II hero "MacArthur" (1977) and the despicable Dr. Joseph Mengele in "The Boys of Brazil" (1978), a role that alienate some of his fans.

A lifelong Democrat, Peck acquired the reputation as Hollywood's house liberal, a fact which earned him a spot on fellow Californian Richard Nixon's infamous enemies list and later made him Ronald Reagan's "former friend." As his film career wound down, his philanthropic efforts in support of arts organizations flowered, with Peck working tirelessly as a founder of the American Film Institute, three-term president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and member of the National Council of Arts, making him seem less an actor than a politician. As such, it seemed fitting that the two Pecks finally melded when he was cast in his first dramatic television role, playing Abraham Lincoln in the four-part miniseries "The Blue and the Grey" (CBS, 1982). He next was a priest saving Jews in World War II in "The Scarlet and the Black" (CBS, 1983) and made a cameo as the U.S. President in the anti-nuclear film, "Amazing Grace and Chuck" (1987). Back on the big screen, he starred opposite Jane Fonda and Jimmy Smits in "Old Gringo" (1989) and played the lawyer for Max Cady (Robert De Niro) in Martin Scorsese's remake of "Cape Fear" (1991).

Still active well into his eighties, Peck executive produced "The Portrait" (TNT, 1993), an adaptation of Tina Howe's play "Painting Churches" directed by Arthur Penn. It was his last starring vehicle, in which Peck played an aging poet opposite Lauren Bacall as his wife and real-life daughter Cecilia Peck as his painter daughter. Having played Starbuck in a college production of Melville's epic and bedeviled the great white whale as Ahab in the 1956 feature, he couldn't pass up the opportunity to act a third time in "Moby Dick, " earning an Emmy nomination for his turn as the fire-and-brimstone preacher - played by Orson Welles in John Ford's movie - in the 1998 version broadcast on USA Network. The role would prove to be Peck's last fictional turn before the cameras before his death from bronchopneumonia on June 12, 2003 in Los Angeles. He was 87 years old and left behind a glorious career rivaled only by a select few.

TCM | Turner Classic Movies Biography By: Shawn Dwyer

More about Ernest A. Bachrach:

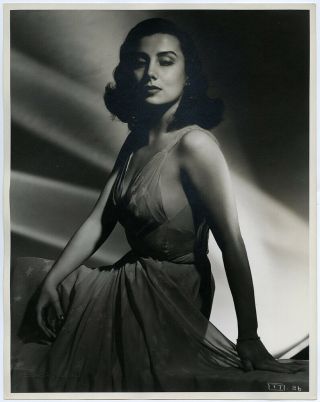

Hollywood’s motion picture still photography defined sophisticated style, shaped personas and created the iconic image of “a movie star” as we know it today. The photographers’ dramatic lighting, dynamic compositions, artful negative retouching and artistic eyes influenced the American public’s perceptions of celebrities and their personalities. Stars were defined as sexy, glamorous, thoughtful, foreboding, all through the scintillating camerawork of these often unsung and forgotten men.

While photographers such as George Hurrell, Ruth Harriet Louise, Clarence Sinclair Bull, Lazslo Willinger and Eugene Robert Richee came to be recognized for their style as well as their artistic sensibilities, RKO’s chief photographer, Ernest Bachrach, gained fame for taking quality portraits that fitted whatever style was requested by art directors or studio publicity chiefs. His discerning eye easily captured the personal essence of the stars he shot, the most important element of a first-rate photographic image. As John Kobal quotes him in his book, “The Art of the Great Hollywood Portrait Photographers, ” “Portraiture is very closely akin to cinematography. The cinematographer has very little need for accessories in the making of close-ups; all he needs is a face and some lights and shadows. And that is all the portrait artist needs. Occasionally — but only occasionally — minor props are useful.”

Ernest Bachrach was born Oct. 20, 1899, in New York, and his early years are mostly unknown, though he did sign up for duty in World War I, starting his service at New York’s Ft. Slocum.

By the early 1920s, he was a stillsman for Famous Players-Lasky at their Astoria, N.Y., studio. John Kobal describes how Gloria Swanson came to admire Bachrach’s work as he shot stills for her New York films. Photographer Robert Coburn told him that for Swanson, “There was no other photographer in the world.”

When Swanson formed her own production company in 1926 and returned to Hollywood, she hired Bachrach to shoot portraits and stills for her films, including “Queen Kelly” (1928), “Sadie Thompson, ” (1928), and “The Trespasser” (1929). After Swanson’s company folded, RKO put him in charge of their newly created portrait gallery, where he would remain for most of his career.

As David Shields relates in his book, “Still: American Silent Motion Picture Photography, ” Bachrach mostly shot stars in full figure before cropping and blowing up images to create head shots, busts, and the like, as did several of his contemporaries like Max Munn Autrey, Ruth Harriet Louise and Jack Freulich. Bachrach focused on capturing expression and thought in his portraits, shaping them to suit whatever a particular medium or outlet required. His images seem alive with possibility as a result. His easygoing, friendly personality and disciplined style endeared him to stars and crew, creating a happy work environment, where his staff called him “Ernie.” His disposition and personality created a loyal, steady work force, including photographers Gaston Longet and Alexander Kahle.

While at RKO, Bachrach shot many of its outstanding stars, including Fred Astaire, Irene Dunne, Ginger Rogers and Katharine Hepburn. He connected particularly with Hepburn, capturing her intelligence, poise and flair in expressive photographs. She comments in Kobal’s book how Bachrach and other stillsmen covered flaws and faults in many women’s faces, creating goddesses out of sometimes ordinary faces.

Bachrach sometimes thought that photographers, along with the studios pushing them to turn out portraits, settled for pretty images that failed to firmly represent a star’s essence or individuality. He described in a 1932 article for American Cinematographer called, “Personality and Pictorialism in Photography, ” what he considered quality portraiture: “A primarily pictorial representation of that person’s personality, made by means of photography.”

Bachrach continually sought to improve his craft, shooting independent work to develop his skills in all areas of photography. Hollywood Reporter stated in its May 3, 1933, issue on his innovation of setting portraits on black mounting “unusually artistic.” He received several awards for his outstanding work, including the International Award at the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago for “Finest portrait work in the world.” The Artists and Fellows of the Royal Photographic Society awarded him a diploma for his “achievement in exceptional graphic studies” at the Fair.

The artist sought to inform and educate his colleagues and the public in lighting, shooting and composing excellent photographs by writing articles for such magazines as American Cinematographer, International Photographer, Popular Photography and Silver Screen. In the July 1939 edition of Silver Screen, Bachrach noted that the first question a photographer should pose to his sitter was, “To whom are you giving it?” Photographs for parents, love interests, or jobs should all be lit and shot differently. Some of his articles focused on shooting for face shapes and body shapes, as well as technical aspects.

Besides shooting portraits, Bachrach often made time to shoot stills for important or artistic RKO films, such as “King Kong, ” “Little Women, ” “Sylvia Scarlett, ” “Citizen Kane, ” “The Secret Fury, ” “The Set-Up” and ‘Holiday Affair.”

Bachrach proudly served in various capacities for Local 659, the Cameraman’s Union, serving for years on its Executive Committee and various committees. He helped establish a cameraman’s salon to provide further opportunities in bettering their skills.

Outside of work, Bachrach focused his shooting skills as the leader of RKO’s crack rifle shooting team, composed of members of the photographic staff. The disciplined shooters placed 13th out of 133 teams in the 1936 United States small bore championship series.

Besides painting with light while shooting portraits, Bachrach also dabbled in actual painting, practicing the discipline of composing art true to life with oils and watercolors as well as chemicals, silver, and light.

By the late 1930s and early 1940s, Bachrach sometimes traveled to the East Coast to shoot portraits or stills for films. While traveling, he often visited with magazine art directors and editors to discern their needs for illustrating articles and covers. He also found time to travel to San Francisco “to make portraits of Katharine Cornell and her troupe in Rose Burke, ” per the Jan. 22, 1942, Variety.

When Local 659 organized a Stills Show with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in the 1940s, Bachrach often achieved recognition for his outstanding work. The photographer won certificates and first-place awards in 1942 and 1943. In 1947, Bachrach cleaned up at the last stills show, winning two first-place and two second-place awards, and the John Leroy Johnston Trophy for most popular still exhibited in the CBS Columbia Square foyer exhibit: an image of Rhonda Fleming superimposed on a human eye.

Bachrach found solace in work after his wife, Rae, died in 1949, staying busy writing articles, making portraits, and serving his union.

In October 1954, Bachrach retired from RKO after 25 years of work to go freelance and enjoy a little free time. He shot stills for “Around the World in 80 Days” and “Run of the Arrow, ” among others.

Ernest Bachrach passed away March 24, 1973, virtually forgotten by the film community. Thanks to the work of photography scholars like John Kobal and Mark Vieira in the 1980s-2000s, his outstanding skills are once again highlighted galleries, articles and books. While not as famous as photographers like George Hurrell, Ruth Harriet Louise, or Clarence Sinclair Bull, Ernest Bachrach ranks as their equal in creating elegant, iconic portraits defining stars’ personas to legions of movie fans around the world.

Biography By: Mary Mallory / Hollywood Heights: Ernest Bachrach Defines RKO Glamour