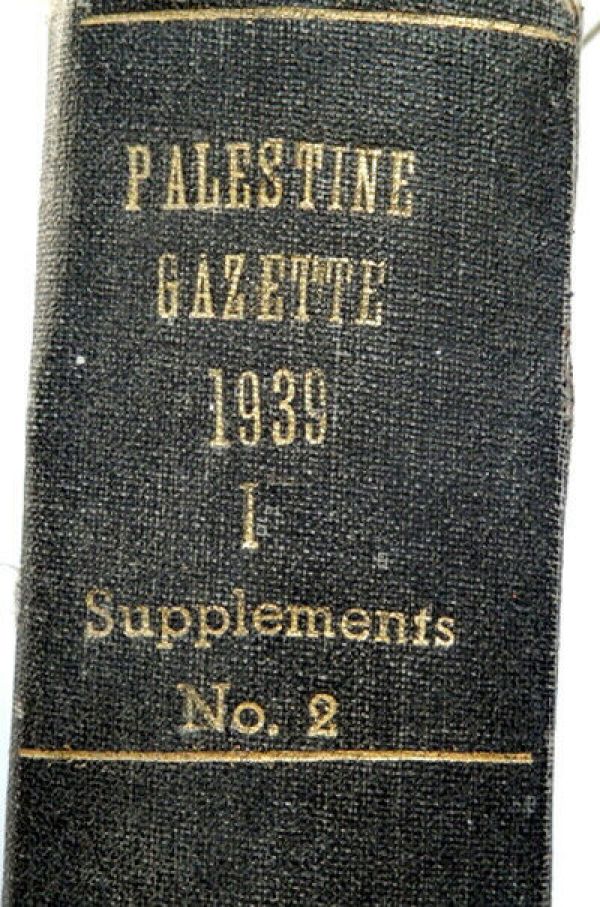

1939 GOVERNMENT OF PALESTINE OFFICIAL GAZETTE SUPPLEMENT VOL BOOK JERUSALEM LAW

Item History & Price

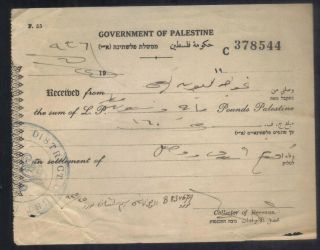

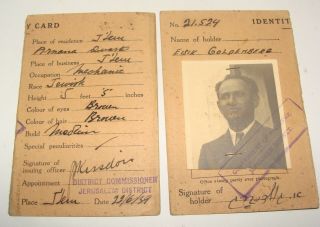

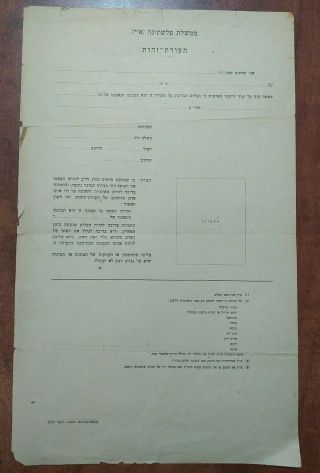

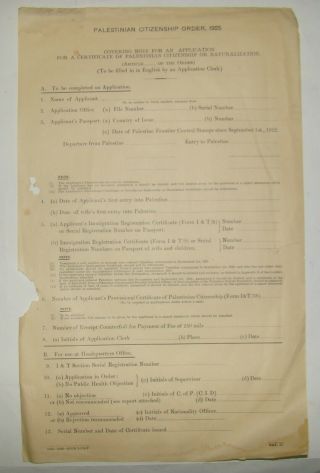

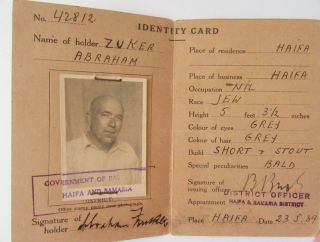

| Reference Number: Avaluer:55412631 | subject: British Mandate in Palestine |

| Religion: Judaism | Country/Region of Manufacture: Israel |

GOVERNMENT OF PALESTINE OFFICIAL GAZETTE SUPPLEMENT JERUSALEM 1939

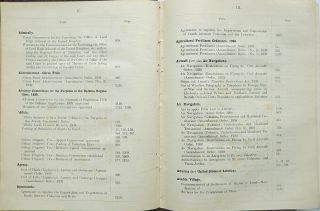

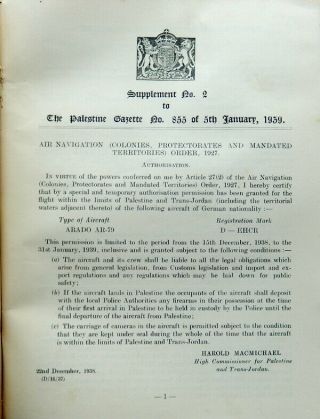

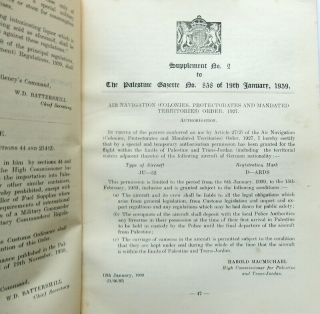

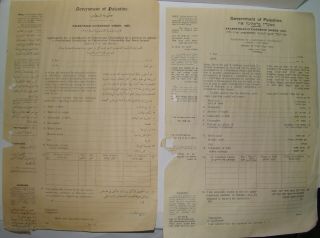

GOVERNMENT OF PALESTINE. Official Gazette, 1939 , Supplement No. 2, total of 32 issues. January -July 1939. Published periodically by the Government of Palestine, the Official Gazette continued to be published up until the creation of the state of Israel, whereby it evolved into "Iton Rishmi". Contains the laws, regulations, ordinances, official statements and notices of the govern...ment of Palestine. Interesting regulations regarding Air Navigations, Traveling, Defence regulations, Immigration, Railway, Customs and more. 148 index pages+ 486 pages. Good condition. Size:24x18cm. Winning bidder pays $24.00 Postage international registered air mail.

Payment accepted via Paypal.

Authenticity 100% GuaranteedPlease have a look at my other listings.Good Luck! Land of Israel (Hebrew: אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל, Modern Eretz Yisrael, Tiberian ʼÉreṣ Yiśrāʼēl) is the traditional Jewish name for an area of indefinite geographical extension in the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Israel (disambiguation)). The definitions of the limits of this territory vary between passages in the Hebrew Bible, with specific mentions in Genesis 15, Exodus 23, Numbers 34 and Ezekiel 47. Nine times elsewhere in the Bible, the settled land is referred as "from Dan to Beersheba, and three times it is referred as "from the entrance of Hamath unto the brook of Egypt” (1 Kings 8:65, 1 Chronicles 13:5 and 2 Chronicles 7:8).". These biblical limits for the land differ from the borders of established historical Israelite and later Jewish kingdoms; over time these have included the United Kingdom of Israel, the two separated kingdoms of Israel (Samaria) and Judah, the Hasmonean Kingdom, and the Herodian Kingdom, which at their heights ruled lands with similar but not identical boundaries. The Jewish religious belief defining the land as where Jewish religious law prevailed and excluding territory where it was not applied, [1] holds that the area is a God-given inheritance of the Jewish people based on the Torah, particularly the books of Genesis and Exodus, as well as on the later Prophets.[2] According to the Book of Genesis, the land was first promised by God to the descendants of Abram; the text is explicit that this is a covenant between God and Abram for his descendants.[3] Abram's name was later changed to Abraham, with the promise refined to pass through his son Isaac and to the Israelites, descendants of Jacob, Abraham's grandson. This belief is not shared by most adherents of replacement theology (or supersessionism), who hold the view that the Old Testament prophecies were superseded by the coming of Jesus, [4] a view often repudiated by Christian Zionists as a theological error.[5] Evangelical Zionists variously claim that Israel has title to the land by divine right, [6] or by a theological, historical and moral grounding of attachment to the land unique to Jews (James Parkes), [7] The idea that ancient religious texts can be warrant or divine right for a modern claim has often been challenged, [8][9] and Israeli courts have rejected land claims based on religious motivations.[10] During the mandatory period (1920-1948) the term "Eretz Yisrael" or the "Land of Israel" was part of the official Hebrew name of Mandatory Palestine. Official Hebrew documents used the Hebrew transliteration of the word “Palestine” פלשתינה (Palestina) followed always by the two initial letters of "Eretz Yisrael", א״י Aleph-Yod.[11][12] The Land of Israel concept has been evoked by the founders of the State of Israel. It often surfaces in political debates on the status of the West Bank, which is referred to in official Israeli discourse as Judea and Samaria, from the names of the two historical Jewish kingdoms.[13] Contents [hide] 1 Etymology and biblical roots 2 Biblical interpretations of the borders 2.1 Genesis 15 2.2 Exodus 23 2.3 Numbers 34 2.4 Deuteronomy 19 2.5 Ezekiel 47 2.6 From Dan to Beersheba 2.7 Division of Tribes 3 Jewish beliefs 3.1 Rabbinic laws in the Land of Israel 3.2 Inheritance of the promise 3.3 Modern Jewish debates on the Land of Israel 4 Christian beliefs 4.1 Inheritance of the promise 5 History 5.1 Ottoman era 5.2 British Mandate 5.3 Israeli period 6 Modern usage 6.1 Usage in Israeli politics 6.2 Palestinian viewpoints 7 See also 8 Notes 9 Further reading 10 External links Etymology and biblical roots 1916 map of the Fertile Crescent by James Henry Breasted. The names used for the land are "Canaan" "Judah" "Palestine" and "Israel" Map of Eretz Israel in 1695 Amsterdam Haggada by Abraham Bar-Jacob. The term "Land of Israel" is a direct translation of the Hebrew phrase ארץ ישראל (Eretz Yisrael), which occurs occasionally in the Bible, [14] and is first mentioned in the Tanakh at 1 Samuel 13:19, following the Exodus, when the Israelite tribes were already in the Land of Canaan.[15] The words are used sparsely in the Bible: King David is ordered to gather 'strangers to the land of Israel'(hag-gêrîm ’ăšer, bə’ereṣ yiśrā’êl) for building purposes (1 Chronicles 22:2), and the same phrasing is used in reference to King Solomon's census of all of the 'strangers in the Land of Israel' (2 Chronicles 2:17). Ezekiel, though generally preferring the phrase 'soil of Israel' (’admat yiśrā’êl), employs eretz israel twice, respectively at Ezekiel 40:2 and Ezekiel 47:18.[16] According to Martin Noth, the term is not an "authentic and original name for this land", but instead serves as "a somewhat flexible description of the area which the Israelite tribes had their settlements".[17]According to Anita Shapira, the term "Eretz Yisrael" was a holy term, vague as far as the exact boundaries of the territories are concerned but clearly defining ownership.[18] The sanctity of the land (kedushat ha-aretz) developed rich associations in rabbinical thought, [19] where it assumes a highly symbolic and mythological status infused with promise, though always connected to a geographical location.[20] Nur Masalha argues that the biblical boundaries are "entirely fictitious", and bore simply religious connotations in Diaspora Judaism, with the term only coming into ascendency with the rise of Zionism.[14] The Hebrew Bible provides three specific sets of borders for the "Promised Land", each with a different purpose. Neither of the terms "Promised Land" (Ha'Aretz HaMuvtahat) or "Land of Israel" are used in these passages: Genesis 15:13–21, Genesis 17:8[21] and Ezekiel 47:13–20 use the term "the land" (ha'aretz), as does Deuteronomy 1:8 in which it is promised explicitly to "Abraham, Isaac and Jacob... and to their descendants after them, " whilst Numbers 34:1–15describes the "Land of Canaan" (Eretz Kna'an) which is allocated to nine and half of the twelve Israelite tribes after the Exodus. The expression "Land of Israel" is first used in a later book, 1 Samuel 13:19. It is defined in detail in the exilic Book of Ezekielas a land where both the twelve tribes and the "strangers in (their) midst", can claim inheritance.[22] The name "Israel" first appears in the Hebrew Bible as the name given by God to the patriarch Jacob (Genesis 32:28). Deriving from the name "Israel", other designations that came to be associated with the Jewish people have included the "Children of Israel" or "Israelite". The term 'Land of Israel' (γῆ Ἰσραήλ) occurs in one episode in the New Testament (Matthew 2:20–21), where, according to Shlomo Sand, it bears the unusual sense of 'the area surrounding Jerusalem'.[21] The section in which it appears was written as a parallel to the earlier Book of Exodus.[23] Biblical interpretations of the borders Genesis 15 (describing "this land") Num. 34 ("Canaan") & Eze. 47 ("this land") Interpretations of the borders of the Promised Land, based on scriptural verses Genesis 15 Genesis 15:18–21 describes what are known as "Borders of the Land" (Gevulot Ha-aretz), [24] which in Jewish tradition defines the extent of the land promised to the descendants of Abraham, through his son Isaac and grandson Jacob.[25] The passage describes the area as the land of the ten named ancient peoples then living there. More precise geographical borders are given Exodus 23:31 which describes borders as marked by the Red Sea (see debate below), the "Sea of the Philistines" i.e., the Mediterranean, and the "River", the Euphrates), the traditional furthest extent of the Kingdom of David.[26][27] Genesis gives the border with Egypt as Nahar Mitzrayim – nahar in Hebrew denotes a large river, never a wadi. Exodus 23 A slightly more detailed definition is given in Exodus 23:31, which describes the borders as "from the sea of reeds (Red Sea) to the Sea of the Philistines (Mediterranean sea) and from the desert to the Euphrates River", though the Hebrew text of the Bible uses the name, "the River", to refer to the Euphrates. Only the "Red Sea" (Exodus 23:31) and the Euphrates are mentioned to define the southern and eastern borders of the full land promised to the Israelites. The "Red Sea" corresponding to Hebrew Yam Suf was understood in ancient times to be the Erythraean Sea, as reflected in the Septuagint translation. Although the English name "Red Sea" is derived from this name ("Erythraean" derives from the Greek for red), the term denoted all the waters surrounding Arabia—including the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf, not merely the sea lying to the west of Arabia bearing this name in modern English. Thus, the entire Arabian peninsula lies within the borders described. Modern maps depicting the region take a reticent view and often leave the southern and eastern borders vaguely defined. The borders of the land to be conquered given in Numbers have a precisely defined eastern border which included the Arabah and Jordan. Numbers 34 Main article: Tribal allotments of Israel Numbers 34:1–15 describes the land allocated to the Israelite tribes after the Exodus. The tribes of Reuben, Gad and half of Manasseh received land east of the Jordan as explained in Numbers 34:14–15. Numbers 34:1–13 provides a detailed description of the borders of the land to be conquered west of the Jordan for the remaining tribes. The region is called "the Land of Canaan" (Eretz Kna'an) in Numbers 34:2 and the borders are known in Jewish tradition as the "borders for those coming out of Egypt". These borders are again mentioned in Deuteronomy 1:6–8, 11:24 and Joshua 1:4. According to the Hebrew Bible, Canaan was the son of Ham who with his descendents had seized the land from the descendents of Shem according to the Book of Jubilees. Jewish tradition thus refers to the region as Canaan during the period between the Flood and the Israelite settlement. Eliezer Schweid sees Canaan as a geographical name, and Israel the spiritual name of the land. He writes: The uniqueness of the Land of Israel is thus "geo-theological" and not merely climatic. This is the land which faces the entrance of the spiritual world, that sphere of existence that lies beyond the physical world known to us through our senses. This is the key to the land's unique status with regard to prophecy and prayer, and also with regard to the commandments.[28] Thus, the renaming of this landmarks a change in religious status, the origin of the Holy Land concept. Numbers 34:1–13 uses the term Canaan strictly for the land west of the Jordan, but Land of Israel is used in Jewish tradition to denote the entire land of the Israelites. The English expression "Promised Land" can denote either the land promised to Abraham in Genesis or the land of Canaan, although the latter meaning is more common. The border with Egypt is given as the Nachal Mitzrayim (Brook of Egypt) in Numbers, as well as in Deuteronomy and Ezekiel. Jewish tradition (as expressed in the commentaries of Rashi and Yehuda Halevi, as well as the Aramaic Targums) understand this as referring to the Nile; more precisely the Pelusian branch of the Nile Delta according to Halevi—a view supported by Egyptian and Assyrian texts. Saadia Gaon identified it as the "Wadi of El-Arish", referring to the biblical Sukkot near Faiyum. Kaftor Vaferech placed it in the same region, which approximates the location of the former Pelusian branch of the Nile. 19th century Bible commentaries understood the identification as a reference to the Wadi of the coastal locality called El-Arish. Easton's, however, notes a local tradition that the course of the river had changed and there was once a branch of the Nile where today there is a wadi. Biblical minimalists have suggested that the Besor is intended. Deuteronomy 19 Deuteronomy 19:8 indicates a certain fluidity of the borders of the promised land when it refers to the possibility that God would "enlarge your borders." This expansion of territory means that Israel would receive "all the land he promised to give to your fathers", which implies that the settlement actually fell short of what was promised. According to Jacob Milgrom, Deuteronomy refers to a more utopian map of the promised land, whose eastern border is the wilderness rather than the Jordan.[29] Paul R. Williamson notes that a "close examination of the relevant promissory texts" supports a "wider interpretation of the promised land" in which it is not "restricted absolutely to one geographical locale." He argues that "the map of the promised land was never seen permanently fixed, but was subject to at least some degree of expansion and redefinition."[30] Ezekiel 47 Ezekiel 47:13–20 provides a definition of borders of land in which the twelve tribes of Israel will live during the final redemption, at the end of days. The borders of the land described by the text in Ezekiel include the northern border of modern Lebanon, eastwards (the way of Hethlon) to Zedad and Hazar-enan in modern Syria; south by southwest to the area of Busra on the Syrian border (area of Hauran in Ezekiel); follows the Jordan River between the West Bank and the land of Gilead to Tamar (Ein Gedi) on the western shore of the Dead Sea; From Tamar to Meribah Kadesh (Kadesh Barnea), then along the Brook of Egypt (see debate below) to the Mediterranean Sea. The territory defined by these borders is divided into twelve strips, one for each of the twelve tribes. Hence, Numbers 34 and Ezekiel 47 define different but similar borders which include the whole of contemporary Lebanon, both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and Israel, except for the South Negev and Eilat. Small parts of Syria are also included. From Dan to Beersheba Further information: From Dan to Beersheba The common biblical phrase used to refer to the territories actually settled by the Israelites (as opposed to military conquests) is "from Dan to Beersheba" (or its variant "from Beersheba to Dan"), which occurs many times in the Bible. It is found in the biblical verses Judges 20:1, 1 Samuel 3:20, 2 Samuel 3:10, 2 Samuel 17:11, 2 Samuel 24:2, 2 Samuel 24:15, 1 Kings 4:25, 1 Chronicles 21:2, and 2 Chronicles 30:5. Division of Tribes The 12 tribes of Israel are divided in 1 Kings 11. In the chapter, King Solomon's sins lead to Israelites forfeiting 10 of the 12 tribes: 30 and Ahijah took hold of the new cloak he was wearing and tore it into twelve pieces. 31 Then he said to Jeroboam, “Take ten pieces for yourself, for this is what the Lord, the God of Israel, says: ‘See, I am going to tear the kingdom out of Solomon’s hand and give you ten tribes. 32 But for the sake of my servant David and the city of Jerusalem, which I have chosen out of all the tribes of Israel, he will have one tribe. 33 I will do this because they have forsaken me and worshiped Ashtoreth the goddess of the Sidonians, Chemosh the god of the Moabites, and Molek the god of the Ammonites, and have not walked in obedience to me, nor done what is right in my eyes, nor kept my decrees and laws as David, Solomon’s father, did.34 “‘But I will not take the whole kingdom out of Solomon’s hand; I have made him ruler all the days of his life for the sake of David my servant, whom I chose and who obeyed my commands and decrees. 35 I will take the kingdom from his son’s hands and give you ten tribes. 36 I will give one tribe to his son so that David my servant may always have a lamp before me in Jerusalem, the city where I chose to put my Name. — Kings 1, 11:30-11:36[31] Jewish beliefs Part of a series on the History of Israel Ancient Israel and Judah PrehistoryCanaanIsraelitesUnited monarchyNorthern KingdomKingdom of JudahBabylonian rule Second Temple period (530 BC–AD 70) Persian ruleHellenistic periodHasmonean dynastyHerodian dynastyKingdomTetrarchy Roman Judea Middle Ages (70–1517) Roman PalaestinaByzantine PalaestinaPrimaSecunda Revolt against HeracliusCaliphates FilastinUrdunn CrusadesAyyubid dynastyMamluk Sultanate Modern history (1517–1948) Ottoman rule EyaletMutasarrifate Old YishuvZionismOETABritish mandate State of Israel (1948–present) IndependenceTimelineYearsArab–Israeli conflictStart-up Nation History of the Land of Israel by topic JudaismJerusalemZionismJewish leadersJewish warfareNationality Related Jewish historyHebrew calendarArchaeologyMuseums Israel portal vte Rabbinic laws in the Land of Israel Main article: Laws and customs of the Land of Israel in Judaism According to Menachem Lorberbaum, In Rabbinic tradition, the land of Israel consecrated by the returning exiles was significantly different in it(s?) boundaries from both the prescribed biblical borders and the actual borders of the pre-Exilic kingdoms. It ranged roughly from Acre in the north to Ashkelon in the south along the Mediterranean, and included Galilee and the Golan. Yet there was no settlement in Samaria.[32] According to Jewish religious law (halakha), some laws only apply to Jews living in the Land of Israel and some areas in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria (which are thought to be part of biblical Israel). These include agricultural laws such as the Shmita (Sabbatical year); tithing laws such as the Maaser Rishon (Levite Tithe), Maaser sheni, and Maaser ani (poor tithe); charitable practices during farming, such as pe'ah; and laws regarding taxation. One popular source lists 26 of the 613 mitzvot as contingent upon the Land of Israel.[33] Many of the religious laws which applied in ancient times are applied in the modern State of Israel; others have not been revived, since the State of Israel does not adhere to traditional Jewish law. However, certain parts of the current territory of the State of Israel, such as the Arabah, are considered by some religious authorities to be outside the Land of Israel for purposes of Jewish law. According to these authorities, the religious laws do not apply there.[34] According to some Jewish religious authorities, every Jew has an obligation to dwell in the Land of Israel and may not leave except for specifically permitted reasons (e.g., to get married).[35] There are also many laws dealing with how to treat the land. The laws apply to all Jews, and the giving of the land itself in the covenant, applies to all Jews, including converts.[36] Inheritance of the promise Traditional religious Jewish interpretation, and that of most Christian commentators, define Abraham's descendants only as Abraham's seed through his son Isaac and his grandson Jacob.[25][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46] Johann Friedrich Karl Keil is less clear, as he states that the covenant is through Isaac, but also notes that Ishmael's descendants, generally the Arabs, have held much of that land through time.[47] Modern Jewish debates on the Land of Israel The Land of Israel concept has been evoked by the founders of the State of Israel. It often surfaces in political debates on the status of the West Bank, which is referred to in official Israeli discourse as Judea and Samaria, from the names of the two historical Israelite and Judean kingdoms.[13] These debates frequently invoke religious principles, despite the little weight these principles typically carry in Israeli secular politics. Ideas about the need for Jewish control of the land of Israel have been propounded by figures such as Rabbi Yitzhak Ginsburg, who has written about the historical entitlement that Jews have to the whole Land of Israel.[48] Ginsburgh's ideas about the need for Jewish control over the land has some popularity within contemporary West Bank settlements.[49] However, there are also strong backlashes from the Jewish community regarding these ideas.[49] The Satmar Hasidic community in particular denounces any geographic or political establishment of Israel, deeming this establishment has directly interfering with God's plan for Jewish redemption. Joel Teitelbaum was a foremost figure in this denouncement, calling the Land and State of Israel a vehicle for idol worship, as well as a smokescreen for Satan's workings.[50] Divisions within the Jewish community concerning Israel speak to how Israel not only represents an international point of contention, but also a continuous ideological and internal introspection and negotiation specific to the Jewish community and its larger history. Christian beliefs Inheritance of the promise During the early 5th century, Saint Augustine of Hippo argued in his City of God that the earthly or "carnal" kingdom of Israel achieved its peak during the reigns of David and his son Solomon.[51] He goes on to say however, that this possession was conditional: "...the Hebrew nation should remain in the same land by the succession of posterity in an unshaken state even to the end of this mortal age, if it obeyed the laws of the Lord its God." He goes on to say that the failure of the Hebrew nation to adhere to this condition resulted in its revocation[citation needed] and the making of a second covenant and cites Jeremiah 31:31–32: "Behold, the days come, says the Lord, that I will make for the house of Israel, and for the house of Judah, a new testament: not according to the testament that I settled for their fathers in the day when I laid hold of their hand to lead them out of the land of Egypt; because they continued not in my testament, and I regarded them not, says the Lord." Augustine concludes that this other promise, revealed in the New Testament, was about to be fulfilled through the incarnation of Christ: "I will give my laws in their mind, and will write them upon their hearts, and I will see to them; and I will be to them a God, and they shall be to me a people". Notwithstanding this doctrine stated by Augustine and also by the Apostle Paul in his Epistle to the Romans (Ch. 11), the phenomenon of Christian Zionism is widely noted today, especially among evangelical Protestants. Other Protestant groups and churches reject Christian Zionism on various grounds. History Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.[52] Nonetheless, during two millennia of exile and with a continuous yet small Jewish presence in the land, a strong sense of bondedness exists throughout this tradition, expressed in terms of people-hood; from the very beginning, this concept was identified with that ancestral biblical land or, to use the traditional religious and modern Hebrew term, Eretz Yisrael. Religiously and culturally the area was seen broadly as a land of destiny, and always with hope for some form of redemption and return. It was later seen as a national home and refuge, intimately related to that traditional sense of people-hood, and meant to show continuity that this land was always seen as central to Jewish life, in theory if not in practice.[53] Ottoman era Main articles: Ottoman Syria and Zionism Having already used another religious term of great importance, Zion (Jerusalem), to coin the name of their movement, being associated with the return to Zion.[54] The term was considered appropriate for the secular Jewish political movement of Zionism to adopt at the turn of the 20th century; it was used to refer to their proposed national homeland in the area then controlled by the Ottoman Empire. As originally stated, "The aim of Zionism is to create for the Jewish people a home in Palestinesecured by law."[55] Different geographic and political definitions for the "Land of Israel" later developed among competing Zionist ideologies during their nationalist struggle. These differences relate to the importance of the idea and its land, as well as the internationally recognized borders of the State of Israel and the Jewish State's secure and democratic existence. Many current governments, politicians and commentators question these differences. British Mandate Three proposals for the post World War I administration of Palestine. The red line is the "International Administration" proposed in the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement, the dashed blue line is the 1919 Zionist Organizationproposal at the Paris Peace Conference, and the thin blue line refers to the final borders of the 1923–48 Mandatory Palestine. This 1920 stamp, issued by the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, set a precedent for the wording of subsequent Mandate stamps. The Biblical concept of Eretz Israel, and its re-establishment as a state in the modern era, was a basic tenet of the original Zionistprogram. This program however, saw little success until the British acceptance of "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people" in the Balfour Declaration of 1917. Chaim Weizmann, as leader of the Zionist delegation, at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference presented a Zionist Statement on 3 February. Among other things, he presented a plan for development together with a map of the proposed homeland. The statement noted the Jewish historical connection with "Palestine".[56] It also declared the Zionists' proposed borders and resources "essential for the necessary economic foundation of the country" including "the control of its rivers and their headwaters". These borders included present day Israel and the occupied territories, western Jordan, southwestern Syria and southern Lebanon "in the vicinity south of Sidon".[57] The subsequent British occupation and British acceptance of the July 1922 League of Nations Mandate for Palestine, [58] advanced the Zionist cause.[citation needed] Early in the deliberations toward British civilian administration, two fundamental decisions were taken, which bear upon the status of the Jews as a nation; the first was the recognition of Hebrew as an official language, along with English and Arabic, and the second concerned the Hebrew name of the country. In 1920, the Jewish members of the first High Commissioner's advisory council objected to the Hebrew transliteration of the word “Palestine” פלשתינה (Palestina) on the ground that the traditional name was ארץ ישראל (Eretz Yisrael), but the Arab members would not agree to this designation, which in their view, had political significance. The High Commissioner Herbert Samuel, himself a Zionist, decided that the Hebrew transliteration should be used, followed always by the two initial letters of "Eretz Yisrael, ” א״י Aleph-Yod:[59] He was aware that there was no other name in the Hebrew language for this land except 'Eretz-Israel'. At the same time he thought that if 'Eretz-Israel' only were used, it might not be regarded by the outside world as a correct rendering of the word 'Palestine', and in the case of passports or certificates of nationality, it might perhaps give rise to passports or certificates of nationality, it might perhaps give rise to difficulties, so it was decided to print 'Palestine' in Hebrew letters and to add after it the letters 'Aleph' 'Yod', which constitute a recognised abbreviation of the Hebrew name. His Excellency still thought that this was a good compromise. Dr. Salem wanted to omit 'Aleph' 'Yod' and Mr. Yellin wanted to omit 'Palestine'. The right solution would be to retain both." —Minutes of the meeting on November 9, 1920.[60] The compromise was later noted as among Arab grievances before the League's Permanent Mandate Commission.[61] During the Mandate, the name Eretz Yisrael (abbreviated א״י Aleph-Yod), was part of the official name for the territory, when written in Hebrew. These official names for Palestine were minted on the Mandate coins and early stamps (pictured) in English, Hebrew "(פלשתינה (א״י" (Palestina E"Y) and Arabic "( فلسطين"). Consequently, in 20th century political usage, the term "Land of Israel" usually denotes only those parts of the land which came under the British mandate.[62] On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution (United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181(II)) recommending "to the United Kingdom, as the mandatory Power for Palestine, and to all other Members of the United Nations the adoption and implementation, with regard to the future government of Palestine, of the Plan of Partition with Economic Union." The Resolution contained a plan to partition Palestine into "Independent Arab and Jewish States and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem."[63] Israeli period On May 14, 1948, the day the British Mandate over Palestine expired, the Jewish People's Council gathered at the Tel Aviv Museum, and approved a proclamation, in which it declared "the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel."[64] When Israel was founded in 1948, the majority Labor leadership, which governed for three decades after independence, accepted the partition of the previous British Mandate of Palestine into independent Jewish and Arab states as a pragmatic solution to the political and demographic issues of the territory, with the description Land of Israel applying to the territory of the State of Israel within the Green Line.[citation needed] The then opposition revisionists, who evolved into today's Likud party, however, regarded the rightful Land of Israel as Eretz Yisrael Ha-Shlema (literally, the whole Land of Israel), which came to be referred to as Greater Israel.[65] Joel Greenberg, writing in The New York Times relates subsequent events this way:[65] The seed was sown in 1977, when Menachem Begin of Likud brought his party to power for the first time in a stunning election victory over Labor. A decade before, in the 1967 war, Israeli troops had in effect undone the partition accepted in 1948 by overrunning the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Ever since, Mr. Begin had preached undying loyalty to what he called Judea and Samaria (the West Bank lands) and promoted Jewish settlement there. But he did not annex the West Bank and Gaza to Israel after he took office, reflecting a recognition that absorbing the Palestinians could turn Israel it into a binational state instead of a Jewish one. Following the Six Day War in 1967, the 1977 elections and the Oslo Accords, the term Eretz Israel became increasingly associated with right-wing expansionist groups who sought to conform the borders of the State of Israel with the biblical Eretz Yisrael.[66] Modern usage Usage in Israeli politics Early government usage of the term, following Israel's establishment, continued the historical link and possible Zionist intentions. In 1951–2 David Ben-Gurion wrote "Only now, after seventy years of pioneer striving, have we reached the beginning of independence in a part of our small country."[67] Soon afterwards he wrote "It has already been said that when the State was established it held only six percent of the Jewish people remaining alive after the Nazi cataclysm. It must now be said that it has been established in only a portion of the Land of Israel. Even those who are dubious as to the restoration of the historical frontiers, as fixed and crystallised and given from the beginning of time, will hardly deny the anomaly of the boundaries of the new State."[68] The 1955 Israeli government year-book said, "It is called the 'State of Israel' because it is part of the Land of Israel and not merely a Jewish State. The creation of the new State by no means derogates from the scope of historical Eretz Israel".[69] Herut and Gush Emunim were among the first Israeli political parties basing their land policies on the Biblical narrative discussed above. They attracted attention following the capture of additional territory in the 1967 Six-Day War. They argue that the West Bank should be annexed permanently to Israel for both ideological and religious reasons. This position is in conflict with the basic "land for peace" settlement formula included in UN242. The Likud party, in the platform it maintained until prior to the 2013 elections, had proclaimed its support for maintaining Jewish settlement communities in the West Bank and Gaza, as the territory is considered part of the historical land of Israel.[70] In her 2009 bid for Prime Minister, Kadima leader Tzipi Livni used the expression, noting, "we need to give up parts of the Land of Israel", in exchange for peace with the Palestinians and to maintain Israel as a Jewish state; this drew a clear distinction with the position of her Likud rival and winner, Benjamin Netanyahu.[71] However, soon after winning the 2009 elections, Netanyahu delivered an address[72] at the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University that was broadcast live in Israel and across parts of the Arab world, on the topic of the Middle East peace process. He endorsed for the first time the notion of a Palestinian state alongside Israel, while asserting the right to a sovereign state in Israel arises from the land being "the homeland of the Jewish people".[73] The Israel–Jordan Treaty of Peace, signed on 1993, led to the establishment of an agreed border between the two nations, and subsequently the state of Israel has no territorial claims in the parts of the historic Land of Israel lying east of the Jordan river. ***** Palestine (Arabic: فلسطين Filasṭīn, Falasṭīn, Filisṭīn; Greek: Παλαιστίνη, Palaistinē; Latin: Palaestina; Hebrew: פלשתינה Palestina) is a geographic region in Western Asia between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. It is sometimes considered to include adjoining territories. The name was used by Ancient Greek writers, and it was later used for the Roman province Syria Palaestina, the Byzantine Palaestina Prima, and the Islamic provincial district of Jund Filastin. The region comprises most of the territory claimed for the biblical regions known as the Land of Israel (Hebrew: ארץ־ישראל Eretz-Yisra'el), the Holy Land or Promised Land. Historically, it has been known as the southern portion of wider regional designations such as Canaan, Syria, ash-Sham, and the Levant. Situated at a strategic location between Egypt, Syria and Arabia, and the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity, the region has a long and tumultuous history as a crossroads for religion, culture, commerce, and politics. The region has been controlled by numerous peoples, including Ancient Egyptians, Canaanites, Israelites and Judeans, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Ancient Greeks and Macedonians, the Jewish Hasmonean Kingdom, Romans, Byzantines, the Arab Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid and Fatimid caliphates, Crusaders, Ayyubids, Mamluks, Mongols, Ottomans, the British, and modern Israelis, Jordanians, Egyptians and Palestinians. The boundaries of the region have changed throughout history. Today, the region comprises the State of Israel and the Palestinian territories in which the State of Palestine was declared. Contents [hide] 1 History of the name 2 History 2.1 Overview 2.2 Ancient period 2.3 Classical antiquity 2.4 Middle Ages 2.5 Ottoman era 2.6 British mandate and partition 2.7 Post–1948 3 Boundaries 3.1 Ancient and Medieval 3.2 Modern period 3.3 Current usage 4 Demographics 4.1 Early demographics 4.2 Late Ottoman and British Mandate periods 4.3 Current demographics 5 See also 6 Notes 7 References 8 Bibliography History of the name Further information: Timeline of the name "Palestine" The name is found throughout recorded history. Examples shown above are (1) Pomponius Mela(Latin, c.43 CE); (2) Notitia Dignitatum (Latin, c.410 CE); (3) Tabula Rogeriana (Arabic, 1154 CE); (4) Cedid Atlas (Ottoman Turkish, 1803 CE) Modern archaeology has identified 12 ancient inscriptions from Egyptian and Assyrian records recording likely cognates of Hebrew Pelesheth. The term "Peleset" (transliterated from hieroglyphs as P-r-s-t) is found in five inscriptions referring to a neighboring people or land starting from c. 1150 BCE during the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt. The first known mention is at the temple at Medinet Habu which refers to the Peleset among those who fought with Egypt in Ramesses III's reign, [1][2] and the last known is 300 years later on Padiiset's Statue. Seven known Assyrian inscriptions refer to the region of "Palashtu" or "Pilistu", beginning with Adad-nirari III in the Nimrud Slab in c. 800 BCE through to a treaty made by Esarhaddon more than a century later.[3][4] Neither the Egyptian nor the Assyrian sources provided clear regional boundaries for the term.[i] The first clear use of the term Palestine to refer to the entire area between Phoenicia and Egypt was in 5th century BC Ancient Greece, [7][8] when Herodotus wrote of a 'district of Syria, called Palaistinê" in The Histories, which included the Judean mountains and the Jordan Rift Valley.[9][ii] Approximately a century later, Aristotle used a similar definition for the region in Meteorology, in which he included the Dead Sea.[11] Later Greek writers such as Polemonand Pausanias also used the term to refer to the same region, which was followed by Roman writers such as Ovid, Tibullus, Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder, Dio Chrysostom, Statius, Plutarch as well as Roman Judean writers Philo of Alexandria and Josephus.[12] The term was first used to denote an official province in c.135 CE, when the Roman authorities, following the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, combined Iudaea Province with Galilee and the Paralia to form "Syria Palaestina". There is circumstantial evidence linking Hadrian with the name change, [13] but the precise date is not certain[13] and the assertion of some scholars that the name change was intended "to complete the dissociation with Judaea"[14] is disputed.[15] The term is generally accepted to be a translation of the Biblical name Peleshet (פלשת Pəlésheth, usually transliterated as Philistia). The term and its derivates are used more than 250 times in Masoretic-derived versions of the Hebrew Bible, of which 10 uses are in the Torah, with undefined boundaries, and almost 200 of the remaining references are in the Book of Judges and the Books of Samuel.[3][4][12][16] The term is rarely used in the Septuagint, who used a transliteration Land of Phylistieim (Γῆ τῶν Φυλιστιείμ) different from the contemporary Greek place name Palaistínē (Παλαιστίνη).[15] The Septuagint instead used the term "allophuloi" (άλλόφυλοι, "other nations") throughout the Books of Judges and Samuel, [17][18] such that the term "Philistines" has been interpreted to mean "non-Israelites of the Promised Land" when used in the context of Samson, Saul and David, [19] and Rabbinic sources explain that these peoples were different from the Philistines of the Book of Genesis.[20] During the Byzantine period, the region of Palestine within Syria Palaestina was subdivided into Palaestina Prima and Secunda, [21] and an area of land including the Negev and Sinai became Palaestina Salutaris.[21] Following the Muslim conquest, place names that were in use by the Byzantine administration generally continued to be used in Arabic.[3][22] The use of the name "Palestine" became common in Early Modern English, [23] was used in English and Arabic during the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem[24][25][iii] and was revived as an official place name with the British Mandate for Palestine. Some other terms that have been used to refer to all or part of this land include Canaan, Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael or Ha'aretz), [27][iv] Greater Syria, the Holy Land, Iudaea Province, Judea, Coele-Syria, [v] "Israel HaShlema", Kingdom of Israel, Kingdom of Jerusalem, Zion, Retenu (Ancient Egyptian), Southern Syria, Southern Levant and Syria Palaestina. History Main article: History of Palestine Further information: Time periods in the Palestine region Overview Situated at a strategic location between Egypt, Syria and Arabia, and the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity, the region has a long and tumultuous history as a crossroads for religion, culture, commerce, and politics. The region has been controlled by numerous peoples, including Ancient Egyptians, Canaanites, Israelites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Ancient Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, the Arab Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid and Fatimid caliphates, Crusaders, Ayyubids, Mamluks, Mongols, Ottomans, the British, and modern Israelis and Palestinians. Modern archaeologists and historians of the region refer to their field of study as Levantine archaeology. Ancient period Depiction of Biblical Palestine in c. 1020 BCE according to George Adam Smith's 1915 Atlas of the Historical Geography of the Holy Land. Smith's book was used as a reference by Lloyd Georgeduring the negotiations for the British Mandate for Palestine.[33] The region was among the earliest in the world to see human habitation, agricultural communities and civilization.[34] During the Bronze Age, independent Canaanite city-states were established, and were influenced by the surrounding civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, Minoan Crete, and Syria. Between 1550–1400 BCE, the Canaanite cities became vassals to the Egyptian New Kingdom who held power until the 1178 BCE Battle of Djahy (Canaan) during the wider Bronze Age collapse.[35] The Israelites emerged from a dramatic social transformation that took place in the people of the central hill country of Canaan around 1200 BCE, with no signs of violent invasion or even of peaceful infiltration of a clearly defined ethnic group from elsewhere.[36][37] The region became part of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from c. 740 BCE, which was itself replaced by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in c. 627 BCE.[38] According to the Bible, a war with Egypt culminated in 586 BCE when Jerusalem was destroyed by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II and the local leaders of the region of Judea were deported to Babylonia. In 539 BCE, the Babylonian empire was replaced by the Achaemenid Empire. According to the Bible and implications from the Cyrus Cylinder, the exiled population of Judea was allowed to return to Jerusalem.[39] Southern Palestine became a province of the Achaemenid Empire, called Idumea, and the evidence from ostraca suggests that a Nabataean-type society, since the Idumeans appear to be connected to the Nabataeans, took shape in southern Palestine in the 4th century B.C.E., and that the Qedarite Arab kingdompenetrated throughout this area through the period of Persian and Hellenistic dominion.[40] Classical antiquity Herod's Temple in Jerusalem functioned as the spiritual center of the various sects of Second Temple Judaism until it was destroyed in 70 CE. This picture shows the temple as imagined in 1966 in the Holyland Model of Jerusalem. In the 330s BCE, Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great conquered the region, which changed hands several times during the wars of the Diadochi and later Syrian Wars. It ultimately fell to the Seleucid Empire between 219–200 BCE. In 116 BCE, a Seleucid civil war resulted in the independence of certain regions including the Hasmonean principality in the Judaean Mountains.[41] From 110 BCE, the Hasmoneans extended their authority over much of Palestine, creating a Judaean–Samaritan–Idumaean–Ituraean–Galilean alliance.[42]The Judaean (Jewish, see Ioudaioi) control over the wider region resulted in it also becoming known as Judaea, a term that had previously only referred to the smaller region of the Judaean Mountains.[43][44] Between 73–63 BCE, the Roman Republicextended its influence into the region in the Third Mithridatic War, conquering Judea in 63 BCE, and splitting the former Hasmonean Kingdom into five districts. The three-year Ministry of Jesus, culminating in his crucifixion, is estimated to have occurred from 28–30 CE, although the historicity of Jesus is disputed by a minority of scholars.[vi] In 70 CE, Titus sacked Jerusalem, resulting in the dispersal of the city's Jews and Christians to Yavne and Pella. In 132 CE, Hadrian joined the province of Iudaea with Galilee and the Paralia to form new province of Syria Palaestina, and Jerusalem was renamed "Aelia Capitolina". Between 259–272, the region fell under the rule of Odaenathus as King of the Palmyrene Empire. Following the victory of Christian emperor Constantine in the Civil wars of the Tetrarchy, the Christianization of the Roman Empire began, and in 326, Constantine's mother Saint Helena visited Jerusalem and began the construction of churches and shrines. Palestine became a center of Christianity, attracting numerous monks and religious scholars. The Samaritan Revolts during this period caused their near extinction. In 614 CE, Palestine was annexed by another Persian dynasty; the Sassanids, until returning to Byzantine control in 628 CE.[46] Middle Ages The Dome of the Rock, the world's first great work of Islamic architecture, constructed in 691. Minaret of the White Mosquein Ramla, constructed in 1318 Arab architecture in the Middle Ages Palestine was conquered by the Islamic Caliphate, beginning in 634 CE.[47] In 636, the Battle of Yarmouk during the Muslim conquest of the Levant marked the start of Muslim hegemony over the region, which became known as Jund Filastin within the province of Bilâd al-Shâm (Greater Syria).[48] In 661, with the Assassination of Ali, Muawiyah I became the Caliph of the Islamic world after being crowned in Jerusalem.[49]The Dome of the Rock, completed in 691, was the world's first great work of Islamic architecture.[50] The majority of the population was Christian and was to remain so until the conquest of Saladin in 1187. The Muslim conquest apparently had little impact on social and administrative continuities for several decades.[51][52][53][vii] The word 'Arab' at the time referred predominantly to Bedouin nomads, though Arab settlement is attested in the Judean highlands and near Jerusalem by the 5th century, and some tribes had converted to Christianity.[55] The local population engaged in farming, which was considered demeaning, and were called Nabaț, referring to Aramaic-speaking villagers. A ḥadīth, brought in the name of a Muslim freedman who settled in Palestine, ordered the Muslim Arabs not to settle in the villages, "for he who abides in villages it is as if he abides in graves".[56] The Umayyads, who had spurred a strong economic resurgence in the area, [57] were replaced by the Abbasids in 750. Ramla became the administrative centre for the following centuries, while Tiberias became a thriving centre of Muslim scholarship.[58] From 878, Palestine was ruled from Egypt by semi-autonomous rulers for almost a century, beginning with the Turkish freeman Ahmad ibn Tulun, for whom both Jews and Christians prayed when he lay dying[59] and ending with the Ikhshidid rulers. Reverence for Jerusalem increased during this period, with many of the Egyptian rulers choosing to be buried there.[60] However, the later period became characterized by persecution of Christians as the threat from Byzantium grew.[61] The Fatimids, with a predominantly Berber army, conquered the region in 970, a date that marks the beginning of a period of unceasing warfare between numerous enemies, which destroyed Palestine, and in particular devastating its Jewish population.[62] Between 1071-73, Palestine was captured by the Great Seljuq Empire, [63] only to be recaptured by the Fatimids in 1098, [64] who then lost the region to the Crusaders in 1099.[65] Their control of Jerusalem and most of Palestine lasted almost a century until their defeat by Saladin's forces in 1187, [66] after which most of Palestine was controlled by the Ayyubids.[66] A rump crusader state in the northern coastal cities survived for another century, but, despite seven further crusades, the Crusaders were no longer a significant power in the region.[67] The Fourth Crusade, which did not reach Palestine, led directly to the decline of the Byzantine Empire, dramatically reducing Christian influence throughout the region.[68] The Crusader fortress in Acre, also known as the HospitallerFortress, was built during the 12th century. The Mamluk Sultanate was indirectly created in Egypt as a result of the Seventh Crusade.[69] The Mongol Empire reached Palestine for the first time in 1260, beginning with the Mongol raids into Palestine under Nestorian Christian general Kitbuqa, and reaching an apex at the pivotal Battle of Ain Jalut, where they were routed by the Mamluks.[70] Ottoman era Main article: History of Palestine § Ottoman era The Khan al-Umdan, constructed in Acre in 1784, is the largest and best preserved caravanserai in the region. In 1486, hostilities broke out between the Mamluks and the Ottoman Empire in a battle for control over western Asia, and the Ottomans conquered Palestine in 1516.[71] Between the mid-16th and 17th centuries, a close-knit alliance of three local dynasties, the Ridwans of Gaza, the Turabays of al-Lajjun and the Farrukhs of Nablus, governed Palestine on behalf of the Porte (imperial Ottoman government).[72] In the 18th century, the Zaydani clan under the leadership of Zahir al-Umar ruled large parts of Palestine autonomously[73] until the Ottomans were able to defeat them in their Galilee strongholds in 1775-76.[74]Zahir had turned the port city of Acre into a major regional power, partly fueled by his monopolization of the cotton and olive oiltrade from Palestine to Europe. Acre's regional dominance was further elevated under Zahir's successor Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar at the expense of Damascus.[75] In 1830, on the eve of Muhammad Ali's invasion, [76] the Porte transferred control of the sanjaks of Jerusalem and Nablus to Abdullah Pasha, the governor of Acre. According to Silverburg, in regional and cultural terms this move was important for creating an Arab Palestine detached from greater Syria (bilad al-Sham).[77] According to Pappe, it was an attempt to reinforce the Syrian front in face of Muhammad Ali's invasion.[78] Two years later, Palestine was conquered by Muhammad Ali's Egypt, [76] but Egyptian rule was challenged in 1834 by a countrywide popular uprising against conscription and other measures considered intrusive by the population.[79] Its suppression devastated many of Palestine's villages and major towns.[80] In 1840, Britain intervened and returned control of the Levant to the Ottomans in return for further capitulations.[81] The death of Aqil Agha marked the last local challenge to Ottoman centralization in Palestine, [82] and beginning in the 1860s, Palestine underwent an acceleration in its socio-economic development, due to its incorporation into the global, and particularly European, economic pattern of growth. The beneficiaries of this process were Arabic-speaking Muslims and Christians who emerged as a new layer within the Arab elite.[83] The end of the 19th century saw the beginning of Zionist immigration and the revival of the Hebrew language and culture.[84] The movement was publicly supported by Great Britain during World War I with the Balfour Declaration of 1917.[85] British mandate and partition The new era in Palestine. The arrival of Herbert Samuelas the first High Commissioner for Palestinein 1920. Samuel had promoted Zionism within the British Cabinet, beginning with his 1915 memorandum entitled The Future of Palestine. Beside him are Lawrence of Arabia, Emir Abdullah, Air Marshal Salmond and Wyndham Deedes. Further information: History of Zionism and History of Israel Palestine passport and Palestine coin. The Mandatory authorities agreed a compromise position regarding the Hebrew name: in English and Arabic the name was simply "Palestine" ("فلسطين"), but the Hebrew version "(פלשתינה)" also included the acronym "(א״י)" for Eretz Yisrael (Land of Israel). The British began their Sinai and Palestine Campaign in 1915.[86] The war reached southern Palestine in 1917, progressing to Gaza and around Jerusalem by the end of the year.[86] The British secured Jerusalem in December 1917.[87] They moved into the Jordan valley in 1918 and a campaign by the Entente into northern Palestine led to victory at Megiddo in September.[87] The British were formally awarded the mandate to govern the region in 1922.[88] The non-Jewish Palestinians revolted in 1920, 1929, and 1936.[89] In 1947, following World War II and The Holocaust, the British Government announced its desire to terminate the Mandate, and the United Nations General Assembly adopted in November 1947 a Resolution 181(II) recommending partition into an Arab state, a Jewish state and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem.[90] The Jewish leadership accepted the proposal, but the Arab Higher Committee rejected it; a civil war began immediately after the Resolution's adoption. The State of Israel was declared in May 1948.[91] Post–1948 In the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Israel captured and incorporated a further 26% of the Mandate territory, Jordan captured the region of Judea and Samaria, [92][93][94] renaming it the "West Bank", while the Gaza Strip was captured by Egypt.[95][96] Following the 1948 Palestinian exodus, also known as al-Nakba, the 700, 000 Palestinians who fled or were driven from their homes were not allowed to return following the Lausanne Conference of 1949.[97] In the course of the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel captured the rest of Mandate Palestine from Jordan and Egypt, and began a policy of establishing Jewish settlements in those territories. From 1987 to 1993, the First Palestinian Intifada against Israel took place, which included the Declaration of the State of Palestine in 1988 and ended with the 1993 Oslo Peace Accords and the creation of the Palestinian National Authority. In 2000, the Second Intifada (also called al-Aqsa Intifada) began, and Israel built a separation barrier. In the 2005 Israeli disengagement from Gaza, Israel withdrew all settlers and military presence from the Gaza Strip, but maintained military control of numerous aspects of the territory including its borders, air space and coast. Israel's ongoing military occupation of the Gaza Strip, the West Bank and East Jerusalem continues to be the world's longest military occupation in modern times.[viii][ix] In November 2012, the status of Palestinian delegation in the United Nations was upgraded to non-member observer state as the State of Palestine.[108][x] Boundaries Satellite image of the region of Palestine, 2003. Ancient and Medieval The boundaries of Palestine have varied throughout history.[xi][xii] The Jordan Rift Valley (comprising Wadi Arabah, the Dead Sea and River Jordan) has at times formed a political and administrative frontier, even within empires that have controlled both territories.[111] At other times, such as during certain periods during the Hasmonean and Crusader states for example, as well as during the biblical period, territories on both sides of the river formed part of the same administrative unit. During the Arab Caliphate period, parts of southern Lebanon and the northern highland areas of Palestine and Jordan were administered as Jund al-Urdun, while the southern parts of the latter two formed part of Jund Dimashq, which during the 9th century was attached to the administrative unit of Jund Filastin.[112] The boundaries of the area and the ethnic nature of the people referred to by Herodotus in the 5th century BCE as Palaestina vary according to context. Sometimes, he uses it to refer to the coast north of Mount Carmel. Elsewhere, distinguishing the Syrians in Palestine from the Phoenicians, he refers to their land as extending down all the coast from Phoenicia to Egypt.[113] Pliny, writing in Latin in the 1st century CE, describes a region of Syria that was "formerly called Palaestina" among the areas of the Eastern Mediterranean.[114] Since the Byzantine Period, the Byzantine borders of Palaestina (I and II, also known as Palaestina Prima, "First Palestine", and Palaestina Secunda, "Second Palestine"), have served as a name for the geographic area between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. Under Arab rule, Filastin (or Jund Filastin) was used administratively to refer to what was under the Byzantines Palaestina Secunda (comprising Judaea and Samaria), while Palaestina Prima (comprising the Galilee region) was renamed Urdunn("Jordan" or Jund al-Urdunn).[3] Modern period Nineteenth-century sources refer to Palestine as extending from the sea to the caravan route, presumably the Hejaz-Damascus route east of the Jordan River valley.[115] Others refer to it as extending from the sea to the desert.[115] Prior to the Allied Powers victory in World War I and the Partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, which created the British mandate in the Levant, most of the northern area of what is today Jordan formed part of the Ottoman Vilayet of Damascus (Syria), while the southern part of Jordan was part of the Vilayet of Hejaz.[116] What later became Mandatory Palestine was in late Ottoman times divided between the Vilayet of Beirut (Lebanon) and the Sanjak of Jerusalem.[26] The Zionist Organization provided its definition of the boundaries of Palestine in a statement to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.[117][118] The British administered Mandatory Palestine after World War I, having promised to establish a homeland for the Jewish people. The modern definition of the region follows the boundaries of that entity, which were fixed in the North and East in 1920-23 by the British Mandate for Palestine (including the Transjordan memorandum) and the Paulet–Newcombe Agreement, [27] and on the South by following the 1906 Turco-Egyptian boundary agreement.[119][120] Modern evolution of Palestinevte 1916–1922 proposals: Three proposals for the post World War I administration of Palestine. The red line is the "International Administration" proposed in the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement, the dashed blue line is the 1919 Zionist Organization proposal at theParis Peace Conference, and the thin blue line refers to the final borders of the 1923–48Mandatory Palestine. 1937 proposal: The first official proposal for partition, published in 1937 by the Peel Commission. An ongoing British Mandate was proposed to keep "the sanctity ofJerusalem and Bethlehem", in the form of an enclave from Jerusalem to Jaffa, includingLydda and Ramle. 1947 (proposal): Proposal per the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine (UN General Assembly Resolution 181 (II), 1947), prior to the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The proposal included a Corpus Separatum for Jerusalem, extraterritorial crossroads between the non-contiguous areas, and Jaffa as an Arab exclave. 1947 (actual): Mandatory Palestine, showing Jewish-owned regions in Palestine as of 1947 in blue, constituting 6% of the total land area, of which more than half was held by theJNF and PICA. The Jewish population had increased from 83, 790 in 1922 to 608, 000 in 1946. 1948–1967 (actual): TheJordanian-annexed West Bank(light green) and Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip (dark green), after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, showing 1949 armistice lines. 1967–1994: During the Six-Day War, Israel captured the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and the Golan Heights, together with the Sinai Peninsula (later traded for peace after the Yom Kippur War). In 1980–81 Israelannexed East Jerusalem andthe Golan Heights. Neither Israel's annexation nor Palestine's claim over East Jerusalem has been internationally recognized. 1994–2006: Under the Oslo Accords, the Palestinian National Authority was created to provide civil government in certain urban areas of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. 2006–present: After theIsraeli disengagement from Gaza and clashes between the two main Palestinian partiesfollowing the Hamas electoral victory, two separate executive governments took control in Gaza and the West Bank. Current usage Further information: Palestinian people, Palestinian territories, State of Palestine, and Palestinian National Authority The region of Palestine is the eponym for the Palestinian people and the culture of Palestine, both of which are defined as relating to the whole historical region, usually defined as the localities within the border of Mandatory Palestine. The 1968 Palestinian National Covenant described Palestine as the "homeland of the Arab Palestinian people", with "the boundaries it had during the British Mandate".[121] However, since the 1988 Palestinian Declaration of Independence, the term State of Palestine refers only to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. This discrepancy was described by the Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas as a negotiated concession in a September 2011 speech to the United Nations: "... we agreed to establish the State of Palestine on only 22% of the territory of historical Palestine - on all the Palestinian Territory occupied by Israel in 1967."[122] The term Palestine is also sometimes used in a limited sense to refer to the parts of the Palestinian territories currently under the administrative control of the Palestinian National Authority, a quasi-governmental entity which governs parts of the State of Palestine under the terms of the Oslo Accords.[xiii] Demographics Main article: Demographic history of Palestine Early demographics Year Jews Christians Muslims Total First half 1st century CE Majority – – ~2, 500 5th century Minority Majority – >1st C End 12th century Minority Minority Majority >225 14th century before Black Death Minority Minority Majority 225 14th century after Black Death Minority Minority Majority 150 Historical population table compiled by Sergio DellaPergola.[124] Figures in thousands. Estimating the population of Palestine in antiquity relies on two methods – censuses and writings made at the times, and the scientific method based on excavations and statistical methods that consider the number of settlements at the particular age, area of each settlement, density factor for each settlement. According to Israeli archaeologists Magen Broshi and Yigal Shiloh, the population of ancient Palestine did not exceed one million.[125][126] By 300AD, Christianity had spread so significantly that Jews comprised only a quarter of the population.[66] Late Ottoman and British Mandate periods In the middle of the 1st century of the Ottoman rule, i.e. 1550 AD, Bernard Lewis in a study of Ottoman registers of the early Ottoman Rule of Palestine reports:[127] From the mass of detail in the registers, it is possible to extract something like a general picture of the economic life of the country in that period. Out of a total population of about 300, 000 souls, between a fifth and a quarter lived in the six towns of Jerusalem, Gaza, Safed, Nablus, Ramle, and Hebron. The remainder consisted mainly of peasants, living in villages of varying size, and engaged in agriculture. Their main food-crops were wheat and barley in that order, supplemented by leguminous pulses, olives, fruit, and vegetables. In and around most of the towns there was a considerable number of vineyards, orchards, and vegetable gardens. Year Jews Christians Muslims Total 1533–1539 5 6 145 157 1690–1691 2 11 219 232 1800 7 22 246 275 1890 43 57 432 532 1914 94 70 525 689 1922 84 71 589 752 1931 175 89 760 1, 033 1947 630 143 1, 181 1, 970 Historical population table compiled by Sergio DellaPergola.[124] Figures in thousands. According to Alexander Scholch, the population of Palestine in 1850 was about 350, 000 inhabitants, 30% of whom lived in 13 towns; roughly 85% were Muslims, 11% were Christians and 4% Jews.[128] According to Ottoman statistics studied by Justin McCarthy, the population of Palestine in the early 19th century was 350, 000, in 1860 it was 411, 000 and in 1900 about 600, 000 of whom 94% were Arabs.[129] In 1914 Palestine had a population of 657, 000 Muslim Arabs, 81, 000 Christian Arabs, and 59, 000 Jews.[130] McCarthy estimates the non-Jewish population of Palestine at 452, 789 in 1882; 737, 389 in 1914; 725, 507 in 1922; 880, 746 in 1931; and 1, 339, 763 in 1946.[131] In 1920, the League of Nations' Interim Report on the Civil Administration of Palestine described the 700, 000 people living in Palestine as follows:[132] Of these, 235, 000 live in the larger towns, 465, 000 in the smaller towns and villages. Four-fifths of the whole population are Moslems. A small proportion of these are Bedouin Arabs; the remainder, although they speak Arabic and are termed Arabs, are largely of mixed race. Some 77, 000 of the population are Christians, in large majority belonging to the Orthodox Church, and speaking Arabic. The minority are members of the Latin or of the Uniate Greek Catholic Church, or—a small number—are Protestants. The Jewish element of the population numbers 76, 000. Almost all have entered Palestine during the last 40 years. Prior to 1850, there were in the country only a handful of Jews. In the following 30 years, a few hundreds came to Palestine. Most of them were animated by religious motives; they came to pray and to die in the Holy Land, and to be buried in its soil. After the persecutions in Russia forty years ago, the movement of the Jews to Palestine assumed larger proportions.