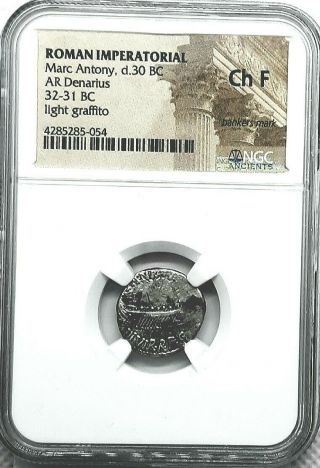

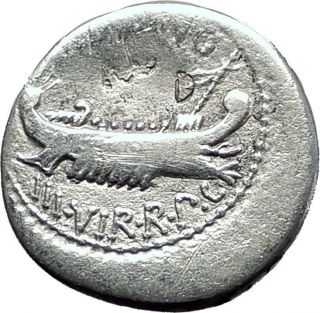

MARK ANTONY & CLEOPATRA Legion Ship Augustus Ancient Silver Roman Coin I39135

Item History & Price

| Reference Number: Avaluer:6794740 |

Item: i39135

Authentic Ancient Coin of: Mark Antony

Silver Denarius 17mm (2.60 grams)

Struck at Actium 32-31 B.C. for Marc Antony's Legion

ANT AVG III VIR R P C, Praetorian galley right.

LEG, Legionary eagle between two standards.

* Numismatic Note: This coin was struck by Antony for the use of his f...leet and legions when he was preparing for the struggle with Octavian. These coins furnish an interesting record of the number of legions of which Antony's army was composed. These denarii are of baser metal than the ordinary currency of the time and might be described as "money of necessity."You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity. Agalley is a type ofship propelled byrowers that originated in the easternMediterranean Sea and was used forwarfare, trade andpiracy from the first millennium BC. Galleys dominatednaval warfare in the Mediterranean from the 8th century BC until development of advanced sailing warships in the 17th century. Galleys fought in the wars ofAssyria, ancientPhoenicia, Greece, Carthage andRome until the 4th century AD. After the fall of theWestern Roman Empire galleys formed the mainstay of theByzantine navy and other navies of successors of the Roman Empire, as well as newMuslim navies. Medieval Mediterranean states, notably the Italian maritime republics, includingVenice, Pisa, Genoa and theOttoman Empire relied on them as the primary warships of their fleets until the 17th century, when they were gradually replaced by sailing warships. Galleys continued to be applied in minor roles in the Mediterranean and theBaltic Sea even after the introduction ofsteam propelled ships in the early 19th century.The galley engagements atActium andLepanto are among the greatestnaval battles in history. An aquila, or eagle, was a prominent symbol used in ancient Rome, especially as thestandard of aRoman legion. Alegionary known as anaquilifer, or eagle-bearer, carried this standard. Each legion carried one eagle. Roman ornament with an aquila (100–200 AD) from the Cleveland Museum of Art . The eagle was extremely important to the Roman military, beyond merely being a symbol of a legion. A lost standard was considered an extremely grave occurrence, and the Roman military often went to great lengths to both protect a standard and to recover it if lost; for example, see the aftermath of theBattle of the Teutoburg Forest, where the Romans spent decades attempting to recover the lost standards of three legions. A modern reconstruction of an aquila HistoryThe signa militaria were the Roman militaryensigns orstandards. The most ancient standard employed by the Romans is said to have been a handful (manipulus) of straw fixed to the top of a spear or pole. Hence the company of soldiers belonging to it was called a maniple. The bundle ofhay or fern was soon succeeded by the figures of animals, of whichPliny the Elder (H.N. x.16) enumerates five: the eagle, thewolf, the ox with the man's head, thehorse, and theboar. In the second consulship ofGaius Marius (104 BC) the four quadrupeds were laid aside as standards, the eagle (Aquila) alone being retained. It was made of silver, orbronze, with outstretched wings, but was probably of a relatively small size, since a standard-bearer (signifer) under Julius Caesar is said in circumstances of danger to have wrenched the eagle from its staff and concealed it in the folds of his girdle.Under the later emperors the eagle was carried, as it had been for many centuries, with the legion, a legion being on that account sometimes calledaquila (Hirt. Bell. Hisp. 30). Eachcohort had for its own ensign theserpent ordragon, which was woven on a square piece of cloth textilis anguis, elevated on agilt staff, to which a cross-bar was adapted for the purpose, and carried by the draconarius.Another figure used in the standards was a ball (orb), supposed to have been emblematic of the dominion of Rome over the world; and for the same reason a bronze figure ofVictoria was sometimes fixed at the top of the staff, as we see it sculptured, together with small statues of Mars, on theColumn of Trajan and theArch of Constantine. Under the eagle or other emblem was often placed a head of the reigning emperor, which was to the army the object of idolatrous adoration.[9] The name of the emperor, or of him who was acknowledged as emperor, was sometimes inscribed in the same situation. The pole used to carry the eagle had at its lower extremity an iron point (cuspis) to fix it in the ground, and to enable the aquilifer in case of need to repel an attack.The minor divisions of a cohort, called centuries, had also each an ensign, inscribed with the number both of the cohort and of the century. This, together with the diversities of the crests worn by the centurions, enabled each soldier to take his place with ease. Denarius minted by Mark Antony to pay his legions. On the reverse, the aquila of his Third legion . In theArch of Constantine at Rome there are four sculptured panels near the top which exhibit a great number of standards and illustrate some of the forms here described. The first panel represents Trajan giving a king to the Parthians: seven standards are held by the soldiers. The second, containing five standards, represents the performance of the sacrifice calledsuovetaurilia.When Constantine embraced Christianity, a figure or emblem of Christ, woven in gold upon purple cloth, was substituted for the head of the emperor. This richly ornamented standard was called labarum. The labarum is still used today by theOrthodox Church in the Sunday service. The entry procession of the chalice whose contents will soon become holy communion is modeled after the procession of the standards of the Roman army. Eagle and weapons from an Augustan-era funerary monument, probably that of Messalla (Prado, Madrid ) Even after the adoption of Christianity as the Roman Empire's religion, the Aquila eagle continued to be used as a symbol. During the reign ofEastern Roman EmperorIsaac I Komnenos, the single-headed eagle was modified todouble-headed to symbolise the Empire's dominance overEast and West.Since the movements of a body of troops and of every portion of it were regulated by the standards, all the evolutions, acts, and incidents of the Roman army were expressed by phrases derived from this circumstance. Thus signa inferre meant to advance, [15]referre to retreat, and convertere to face about; efferre, or castris vellere, to march out of the camp; ad signa convenire, to re-assemble. Notwithstanding some obscurity in the use of terms, it appears that, whilst the standard of the legion was properly called aquila, those of the cohorts were in a special sense of the term called signa, their bearers being signiferi, and that those of the manipuli or smaller divisions of the cohort were denominated vexilla, their bearers being vexillarii. Also, those who fought in the first ranks of the legion before the standards of the legion and cohorts were called antesignani.In military stratagems it was sometimes necessary to conceal the standards. Although the Romans commonly considered it a point of honour to preserve their standards, in some cases of extreme danger the leader himself threw them among the ranks of the enemy in order to divert their attention or to animate his own soldiers. A wounded or dying standard-bearer delivered it, if possible, into the hands of his general, from whom he had received it signis acceptis.Lost Aquilae Battles where the Aquilae were lost, units that lost the Aquilae and the fate of the Aquilae: 53 BC - Battle of Carrhae . Crassus Legio X (returned). 40 BC - defeat of Decidius Saxa at Cilicia (returned). 36 BC - defeat of Mark Antony (returned). 19 BC - Cantabrian Wars at Hispania. Legio I Germanica (thought to have been lost, and stripped of its title "Augusta"). 9 AD - Battle of the Teutoburg Forest . Legio XVII , Legio XVIII , and Legio XIX (all recaptured). 66 - Great Jewish Revolt . Legio XII Fulminata (fate uncertain). 87 - Domitian's Dacian War . Legio V Alaudae (fate uncertain). 132 - Bar Kochva Revolt . Legio XXII Deiotariana (fate uncertain). 161 - Parthians overrun a legion commanded by Severianus at Elegeia in Armenia, possibly the Ninth Legion .[23] Modern imagery Reconstruction of aquila on Roman vexilloid Aquila clutching fasces, a symbol in Italy during the Fascist period Aquila on the coat of arms of Romania Standards Roman military standards. The standards with discs, or signa (first three on left) belong to centuriae of the legion (the image does not show the heads of the standards - whether spear-head or wreathed-palm). Note (second from right) the legion's aquila . The standard on the extreme right probably portrays the She-wolf (lupa) which fed Romulus , the legendary founder of Rome. (This was the emblem of Legio VI Ferrata , a legion then based in Judaea , a detachment of which is known to have fought in Dacia). Detail from Trajan's Column, Rome Modern reenactors parade with replicas of various legionary standards. From left to right: signum (spear-head type), with four discs; signum (wreathed-palm type), with six discs; imago of ruling emperor; legionary aquila; vexillum of commander (legatus) of Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix , with embroidered name and emblem (Capricorn) of legion Each tactical unit in the imperial army, from centuria upwards, had its own standard. This consisted of a pole with a variety of adornments that was borne by dedicated standard-bearers who normally held the rank of duplicarius. Military standards had the practical use of communicating to unit members where the main body of the unit was situated, so that they would not be separated, in the same way that modern tour-group guides use umbrellas or flags. But military standards were also invested with a mystical quality, representing the divine spirit (genius) of the unit and were revered as such (soldiers frequently prayed before their standards). The loss of a unit's standard to the enemy was considered a terrible stain on the unit's honour, which could only be fully expunged by its recovery.The standard of a centuria was known as a signum, which was borne by the unit's signifer. It consisted of a pole topped by either an open palm of a human hand or by a spear-head. The open palm, it has been suggested, originated as a symbol of themaniple (manipulus = "handful"), the smallest tactical unit in theRoman army of the mid-Republic. The poles were adorned with two to six silver discs (the significance of which is uncertain). In addition, the pole would be adorned by a variety of cross-pieces (including, at bottom, a crescent-moon symbol and a tassel). The standard would also normally sport a cross-bar with tassels.[194]The standard of a Praetorian cohort or an auxiliary cohort or ala was known as a vexillum or banner. This was a square flag, normally red in colour, hanging from a crossbar on the top of the pole. Stitched on the flag would be the name of the unit and/or an image of a god. An exemplar found in Egypt bears an image of the goddess Victory on a red background. The vexillum was borne by a vexillarius. A legionary detachment (vexillatio) would also have its own vexillum. Finally, a vexillum traditionally marked the commander's position on the battlefield.[194] The exception to the red colour appears to have been the Praetorian Guard, whosevexilla, similar to their clothing, favoured a blue background.From the time ofMarius (consul 107 BC), the standard of all legions was the aquila ("eagle"). The pole was surmounted by a sculpted eagle of solid gold, or at least gold-plated silver, carrying thunderbolts in its claws (representingJupiter, the highest Roman god. Otherwise the pole was unadorned. No exemplar of a legionary eagle has ever been found (doubtless because any found in later centuries were melted down for their gold content).[194] The eagle was borne by the aquilifer, the legion's most senior standard-bearer. So important were legionary eagles as symbols of Roman military prestige and power, that the imperial government would go to extraordinary lengths to recover those captured by the enemy. This would include launching full-scale invasions of the enemy's territory, sometimes decades after the eagles had been lost e.g. the expedition in 28 BC byMarcus Licinius Crassus againstGenucla (Isaccea, near modernTulcea, Rom., in the Danube delta region), a fortress of the Getae, to recover standards lost 33 years earlier byGaius Antonius, an earlierproconsul ofMacedonia.[195] Or the campaigns of AD 14-17 to recover the three eagles lost byVarus in AD 6 in theTeutoburg Forest.Under Augustus, it became the practice for legions to carry portraits (imagines) of the ruling emperor and his immediate family members. An imago was usually a bronze bust carried on top of a pole like a standard by an imaginifer.From around the time of Hadrian (r. 117-38), some auxiliary alae adopted the dragon-standard (draco) commonly carried by Sarmatian cavalry squadrons. This was a long cloth wind-sock attached to an ornate sculpture of an open dragon's mouth. When the bearer (draconarius) was galloping, it would make a strong hissing-sound.DecorationsThe Roman army awarded a variety of individual decorations (dona) for valour to its legionaries. Hasta pura was a miniature spear; phalerae were large medal-like bronze or silver discs worn on the cuirass; armillae were bracelets worn on the wrist; andtorques were worn round the neck, or on the cuirass. The highest awards were the coronae ("crowns"), of which the most prestigious was thecorona civica, a crown made oak-leaves awarded for saving the life of a fellow Roman citizen in battle. The most valuable award was the corona muralis, a crown made of gold awarded to the first man to scale an enemy rampart. This was awarded rarely, as such a man hardly ever survived.[196]There is no evidence that auxiliary common soldiers received individual decorations like legionaries, although auxiliary officers did. Instead, the whole regiment was honoured by a title reflecting the type of award e.g. torquata ("awarded a torque") or armillata ("awarded bracelets"). Some regiments would, in the course of time, accumulate a long list of titles and decorations e.g. cohors I Brittonum Ulpia torquata pia fidelis c.R..[193]Marcus Antonius, commonly known in English as Mark Antony (Latin:M·ANTONIVS·M·F·M·N)(January 14, 83 BC – August 1, 30 BC), was aRoman politician and general. As a military commander and administrator, he was an important supporter and loyal friend of his mother's cousinJulius Caesar. AfterCaesar's assassination, Antony formed an official political alliance with Octavian (the futureAugustus) andLepidus, known to historians today as theSecond Triumvirate. The triumvirate broke up in 33 BC. Disagreement between Octavian and Antony erupted into civil war, theFinal War of the Roman Republic, in 31 BC. Antony was defeated by Octavian at the navalBattle of Actium, and in a brief land battle atAlexandria. He and his loverCleopatra committed suicide shortly thereafter. His career and defeat are significant in Rome's transformation fromRepublic toEmpire.Early lifeA member of theAntonia clan (gens), Antony was born on January 14, [note 2] mostly likely in 83 BC.Plutarch[1] gives Antony's year of birth as either 86 or 83 BC.[2] Antony was an infant at the time ofSulla's landing atBrundisium in the spring of 83 BC and the subsequent proscriptions that had put the life of the teen-agedJulius Caesar at risk.[3] He was thehomonymous and thus presumably the eldest son ofMarcus Antonius Creticus (praetor 74 BC, proconsul 73–71 BC) and grandson of the noted oratorMarcus Antonius (consul 99 BC, censor 97–6 BC) who had been murdered during theMarian Terror of the winter of 87–6 BC.[4]Antony's father was incompetent and corrupt, and according toCicero, he was only given power because he was incapable of using or abusing it effectively.[5] In 74 BC he was given imperium infinitum to defeat thepirates of theMediterranean, but he died inCrete in 71 BC without making any significant progress.[4][5][6] Creticus had two other sons:Gaius (praetor 44 BC, born c.82 BC) andLucius (quaestor 50 BC, consul 41 BC, born c.81 BC).Antony's mother, Julia, was a daughter ofLucius Caesar (consul 90 BC, censor 89 BC). Upon the death of her first husband, she marriedPublius Cornelius Lentulus (consul 71 BC), an eminent patrician.[7] Lentulus, despite exploiting his political success for financial gain, was constantly in debt due to the extravagance of his lifestyle. He was a major figure in theSecond Catilinarian Conspiracy and was extrajudicially killed on the orders ofCicero in 63 BC.[7]Antony lived a dissipate lifestyle as a youth, and gained a reputation for heavy gambling.[6] According to Cicero, he had a homosexual relationship withGaius Scribonius Curio.[8] There is little reliable information on his political activity as a young man, although it is known that he was an associate ofClodius.[9] He may also have been involved in theLupercal cult, as he was referred to as a priest of this order later in life.[10]In 58 BC, Antony travelled toAthens to studyrhetoric andphilosophy, escaping his creditors. The next year, he was summoned byAulus Gabinius, proconsul ofSyria, to take part in the campaigns againstAristobulus II inJudea, as the commander of aGallic cavalry regiment.[11] Antony achieved important victories atAlexandrium andMachaerus.Supporter of CaesarIn 54 BC, Antony became a staff officer in Caesar's armies inGaul and Germany. He again proved to be a competent military leader in theGallic Wars. Antony and Caesar were the best of friends, as well as being fairly close relatives. Antony made himself ever available to assist Caesar in carrying out his military campaigns.Raised by Caesar's influence to the offices ofquaestor, augur, andtribune of the plebeians (50 BC), he supported the cause of his patron with great energy. Caesar's two proconsular commands, during a period of ten years, were expiring in 50 BC, and he wanted to return to Rome for the consular elections. But resistance from the conservative faction of the Roman Senate, led byPompey, demanded that Caesar resign his proconsulship and the command of his armies before being allowed to seek re-election to the consulship.This Caesar would not do, as such an act would at least temporarily render him a private citizen and thereby leave him open to prosecution for his acts while proconsul. It would also place him at the mercy of Pompey's armies. To prevent this occurrence Caesar bribed the plebeian tribuneCurio to use his veto to prevent a senatorial decree which would deprive Caesar of his armies and provincial command, and then made sure Antony was elected tribune for the next term of office.Antony exercised his tribunician veto, with the aim of preventing a senatorial decree declaring martial law against the veto, and was violently expelled from the senate with another Caesar adherent, Cassius, who was also a tribune of the plebs. Caesar crossed the riverRubicon upon hearing of these affairs which began theRepublican civil war. Antony left Rome and joined Caesar and his armies atAriminium, where he was presented to Caesar's soldiers still bloody and bruised as an example of the illegalities that his political opponents were perpetrating, and as acasus belli.Tribunes of the Plebs were meant to be untouchable and their veto inalienable according to the Romanmos maiorum (although there was a grey line as to what extent this existed in the declaration of and during martial law). Antony commanded Italy whilst Caesar destroyed Pompey's legions in Spain, and led the reinforcements to Greece, before commanding the right wing of Caesar's armies atPharsalus.Administrator of ItalyWhen Caesar becamedictator for a second time, Antony was mademagister equitum, and in this capacity he remained in Italy as the peninsula's administrator in 47 BC, while Caesar was fighting the last Pompeians, who had taken refuge in theprovince of Africa. But Antony's skills as an administrator were a poor match for his generalship, and he seized the opportunity of indulging in the most extravagant excesses, depicted byCicero in the Philippics. In 46 BC he seems to have taken offense because Caesar insisted on payment for the property of Pompey which Antony professedly had purchased, but had in fact simply appropriated.Conflict soon arose, and, as on other occasions, Antony resorted to violence. Hundreds ofcitizens were killed and Rome itself descended into a state of anarchy. Caesar was most displeased with the whole affair and removed Antony from all political responsibilities. The two men did not see each other for two years. The estrangement was not of long continuance, with Antony meeting the dictator atNarbo (45 BC) and rejecting the suggestion ofTrebonius that he should join in the conspiracy that was already afoot. Reconciliation arrived in 44 BC, when Antony was chosen as partner for Caesar's fifth consulship.Whatever conflicts existed between the two men, Antony remained faithful to Caesar but it is worth mentioning that according to Plutarch (paragraph 13) Trebonius, one of the conspirators, had 'sounded him unobtrusively and cautiously...Antony had understood his drift...but had given him no encouragement: at the same time he had not reported the conversation to Caesar'. On February 15, 44 BC, during theLupercalia festival, Antony publicly offered Caesar adiadem. This was an event fraught with meaning: a diadem was a symbol of a king, and in refusing it, Caesar demonstrated that he did not intend to assume the throne.Casca, Marcus Junius Brutus andCassius decided, in the night before theAssassination of Julius Caesar, that Mark Antony should stay alive.[12] The following day, theIdes of March, he went down to warn the dictator but the Liberatores reached Caesar first and he was assassinated on March 15, 44 BC. In the turmoil that surrounded the event, Antony escaped Rome dressed as a slave; fearing that the dictator's assassination would be the start of a bloodbath among his supporters. When this did not occur, he soon returned to Rome, discussing a truce with the assassins' faction. For a while, Antony, as consul, seemed to pursue peace and an end to the political tension. Following a speech by Cicero in the Senate, an amnesty was agreed for the assassins.Caesar's assassination caused widespread discontent among theRoman middle and lower classes with whom Caesar was popular. The mob grew violent at Caesar's funeral and attacked the homes of Brutus and Cassius. Antony, Octavian and Lepidus, capitalised on the mood of theplebians and incited them against theOptimates. Tension escalated and finally spiraled out of control resulting in theLiberators' civil war[13][14]Enemy of the state and triumvirate Roman aureus bearing the portraits of Mark Antony (left) and Octavian (right). Struck in 41 BC, this coin was issued to celebrate the establishment of the Second Triumvirate by Octavian, Antony and Marcus Lepidus in 43 BC. Both sides bear the inscription "III VIR R P C", meaning "One of Three Men for the Regulation of the Republic". Antony, left as sole Consul, surrounded himself with a bodyguard of Caesar's veterans and forced the senate to transfer to him the province ofCisalpine Gaul, which was then administered byDecimus Junius Brutus Albinus, one of the conspirators. Brutus refused to surrender the province and Antony set out to attack him in the beginning of43 BC, besieging him atMutina.Encouraged by Cicero, the Senate denounced Antony and in January 43 they granted Octavian imperium (commanding power), which made his command of troops legal and sent him to relieve the siege, along withAulus Hirtius andGaius Vibius Pansa Caetronianus, the consuls for 43 BC. In April 43, Antony's forces were defeated at theBattles of Forum Gallorum andMutina, forcing Antony to retreat to Transalpine Gaul. However, both consuls were killed, leaving Octavian in sole command of their armies.When they knew that Caesar's assassins, Brutus and Cassius, were assembling an army in order to march on Rome, Antony, Octavian and Lepidus allied in November 43 BC, forming theSecond Triumvirate to stop them.Brutus andCassius were defeated by Antony and Octavian at theBattle of Philippi in October 42 BC. After the battle, a new arrangement was made among the members of the Second Triumvirate: while Octavian returned to Rome, Antony went on to govern the east. Lepidus went on to govern Hispania and the province of Africa. The triumvirate's enemies were subjected toproscription including Mark Antony's archenemy Cicero who was killed on December 7, 43 BC.Antony and CleopatraAntony summonedCleopatra toTarsus in October 41 BC. There they formed an alliance and became lovers. Antony returned to Alexandria with her, where he spent the winter of 41 BC – 40 BC. In spring 40 BC he was forced to return to Rome following news of his wife Fulvia's involvement in civil strife with Octavian on his behalf.Fulvia died while Antony was en route to Sicyon (where Fulvia was exiled). Antony made peace withOctavian in September 40 BC and married Octavian's sisterOctavia Minor.TheParthian Empire had supported Brutus and Cassius in the civil war, sending forces which fought with them at Philippi; following Antony and Octavian's victory, the Parthians invaded Roman territory, occupying Syria, advancing intoAsia Minor and installingAntigonus as puppet king inJudaea to replace the pro-RomanHyrcanus. Antony sent his generalVentidius to oppose this invasion. Ventidius won a series of victories against the Parthians, killing the crown princePacorus and expelling them from the former Roman territories which they had seized. Antony and Octavia on the obverse of a tetradrachm issued in 39 BC at Ephesus; on the reverse, twinned serpents frame a Dionysus who holds a cantharus and thyrsus and stands on a cista mystica Antony now planned to retaliate by invading Parthia, and secured an agreement from Octavian to supply him with extra troops for his campaign. With this military purpose on his mind, Antony sailed to Greece with Octavia, where he behaved in a most extravagant manner, assuming the attributes of theGreekgodDionysus in 39 BC. But the rebellion inSicily ofSextus Pompeius, the last of the Pompeians, kept the army promised to Antony in Italy. With his plans again disrupted, Antony and Octavian quarreled once more. This time with the help ofOctavia, a new treaty was signed inTarentum in 38 BC. The triumvirate was renewed for a period of another five years (ending in 33 BC) and Octavian promised again to send legions to the East.But by now, Antony was skeptical of Octavian's true support of his Parthian cause. Leaving Octavia pregnant with her second child Antonia in Rome, he sailed to Alexandria, where he expected funding from Cleopatra, the mother of his twins. The queen of Egypt lent him the money he needed for the army, and after capturingJerusalem and surrounding areas in 37 BC, he installedHerod as puppet king of Judaea, replacing the Parthian appointee Antigonus.Antony then invaded Parthian territory with an army of about 100, 000 Roman and allied troops but the campaign proved a disaster. After defeats in battle, the desertion of his Armenian allies and his failure to capture Parthian strongholds convinced Antony to retreat, his army was further depleted by the hardships of its retreat throughArmenia in the depths of winter, losing more than a quarter of its strength in the course of the campaign.Meanwhile, in Rome, the triumvirate was no more. Octavian forced Lepidus to resign after the older triumvir attempted an ill-judged political move. Now in sole power, Octavian was occupied in wooing the traditional Republican aristocracy to his side. He marriedLivia and started to attack Antony in order to raise himself to power. He argued that Antony was a man of low morals to have left his faithful wife abandoned in Rome with the children to be with the promiscuous queen of Egypt. Antony was accused of everything, but most of all, of "going native", an unforgivable crime to the proud Romans. Several times Antony was summoned to Rome, but remained in Alexandria with Cleopatra.Again with Egyptian money, Antony invaded Armenia, this time successfully. In the return, a mockRoman Triumph was celebrated in the streets of Alexandria. The parade through the city was apastiche of Rome's most important military celebration. For the finale, the whole city was summoned to hear a very important political statement. Surrounded by Cleopatra and her children, Antony ended his alliance with Octavian.He distributed kingdoms among his children:Alexander Helios was named king ofArmenia, Media andParthia (territories which were not for the most part under the control of Rome), his twinSelene gotCyrenaica andLibya, and the youngPtolemy Philadelphus was awarded Syria andCilicia. As for Cleopatra, she was proclaimed Queen of Kings and Queen of Egypt, to rule withCaesarion (Ptolemy XV Caesar, son of Cleopatra by Julius Caesar), King of Kings and King of Egypt. Most important of all, Caesarion was declared legitimate son and heir of Caesar. These proclamations were known as the Donations of Alexandria and caused a fatal breach in Antony's relations with Rome.While the distribution of nations among Cleopatra's children was hardly a conciliatory gesture, it did not pose an immediate threat to Octavian's political position. Far more dangerous was the acknowledgment of Caesarion as legitimate and heir to Caesar's name. Octavian's base of power was his link with Caesar throughadoption, which granted him much-needed popularity and loyalty of the legions. To see this convenient situation attacked by a child borne by the richest woman in the world was something Octavian could not accept. The triumvirate expired on the last day of 33 BC and was not renewed. Another civil war was beginning.During 33 and 32 BC, a propaganda war was fought in the political arena of Rome, with accusations flying between sides. Antony (in Egypt) divorced Octavia and accused Octavian of being a social upstart, of usurping power, and of forging the adoption papers by Caesar. Octavian responded with treason charges: of illegally keeping provinces that should be given to other men bylots, as was Rome's tradition, and of starting wars against foreign nations (Armenia and Parthia) without the consent of the Senate.Antony was also held responsible forSextus Pompeius' execution with no trial. In 32 BC, the Senate deprived him of his powers and declared war against Cleopatra – not Antony, because Octavian had no wish to advertise his role in perpetuating Rome's internecine bloodshed. Both consuls, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus andGaius Sosius, and a third of the Senate abandoned Rome to meet Antony and Cleopatra in Greece.In 31 BC, the war started. Octavian's loyal and talented generalMarcus Vipsanius Agrippa captured the Greek city and naval port ofMethone, loyal to Antony. The enormous popularity of Octavian with the legions secured the defection of the provinces of Cyrenaica and Greece to his side. On September 2, the navalbattle of Actium took place. Antony and Cleopatra's navy was destroyed, and they were forced to escape to Egypt with 60 ships.The Battle of Actium was the decisive confrontation of theFinal War of the Roman Republic. It was fought between the forces ofOctavian and the combined forces ofMark Antony andCleopatra. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC, on theIonian Sea near the Roman colony ofActium inGreece. Octavian's fleet was commanded byMarcus Vipsanius Agrippa, while Antony's fleet was supported by the ships of his beloved, Cleopatra VII, Queen ofPtolemaic Egypt.Octavian's victory enabled him to consolidate his power over Rome and its dominions. To that end, he adopted the title ofPrinceps ("first citizen") and as a result of the victory was awarded the title ofAugustus by the Roman Senate. As Augustus, he would retain the trappings of a restored Republican leader; however, historians generally view this consolidation of power and the adoption of these honorifics as the end of theRoman Republic and the beginning of theRoman Empire.Octavian, now close to absolute power, did not intend to give them rest. In August 30 BC, assisted by Agrippa, he invaded Egypt. With no other refuge to escape to, Antony committed suicide by stabbing himself with his sword in the mistaken belief that Cleopatra had already done so. When he found out that Cleopatra was still alive, his friends brought him to Cleopatra's monument in which she was hiding, and he died in her arms.Cleopatra was allowed to conduct Antony's burial rites after she had been captured by Octavian. Realising that she was destined for Octavian's triumph in Rome, she made several attempts to take her life and was finally successful in mid-August. Octavian had Caesarion murdered, but he spared Antony's children by Cleopatra, who were paraded through the streets of Rome. Antony's daughters by Octavia were spared, as was his son, Iullus Antonius. But his elder son, Marcus Antonius Antyllus, was killed by Octavian's men while pleading for his life in theCaesareum.Aftermath and legacyCicero's son, Cicero Minor, announced Antony's death to the senate. Antony's honours were revoked and his statues removed (damnatio memoriae). Cicero also made a decree that no member of theAntonii would ever bear the nameMarcus again. “In this way Heaven entrusted the family of Cicero the final acts in the punishment of Antony.”[16]When Antony died, Octavian became uncontested ruler of Rome. In the following years, Octavian, who was known asAugustus after 27 BC, managed to accumulate in his person all administrative, political, and military offices. When Augustus died in 14 AD, his political powers passed to his adopted sonTiberius; the RomanPrincipate had begun.The rise of Caesar and the subsequent civil war between his two most powerful adherents effectively ended the credibility of the Romanoligarchy as a governing power and ensured that all future power struggles would centre upon which one individual would achieve supreme control of the government, eliminating the Senate and the former magisterial structure as important foci of power, in these conflicts. Thus, in history, Antony appears as one of Caesar's main adherents, he and Octavian Augustus being the two men around whom power coalesced following the assassination of Caesar, and finally as one of the three men chiefly responsible for the demise of theRoman Republic.Marriages and issue Fragmentary portrait bust from Smyrna thought to depict Octavia, sister of Octavian and Antony's wife Antony had been married in succession to Fadia, Antonia, Fulvia, Octavia and Cleopatra, and left behind him a number of children. Through his daughters by Octavia, he would be ancestor to theRoman EmperorsCaligula, Claudius andNero. Marriage to Fadia, a daughter of a freedman . According to Cicero , Fadia bore Antony several children. Nothing is known about Fadia or their children. Cicero is the only Roman source that mentions Antony’s first wife. Marriage to first paternal cousin Antonia Hybrida Minor. According to Plutarch , Antony threw her out of his house in Rome, because she slept with his friend, the tribune Publius Cornelius Dolabella . This occurred by 47 BC and Antony divorced her. By Antonia, he had a daughter: Antonia, granddaughter of Gaius Antonius Hybrida , married the wealthy Greek Pythodoros of Tralles . Marriage to Fulvia , by whom he had two sons: Marcus Antonius Antyllus , murdered by Octavian in 30 BC. Iullus Antonius , married Claudia Marcella Major, daughter of Octavia. Marriage to Octavia the Younger , sister of Octavian, later Augustus ; they had two daughters: Antonia Major , married Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (consul 16 BC) ; maternal grandmother of the Empress Valeria Messalina and paternal grandmother of the Emperor Nero . Antonia Minor , married Nero Claudius Drusus , the younger son of the Empress Livia Drusilla and brother of the Emperor Tiberius ; mother of the Emperor Claudius , grandmother of the Emperor Caligula and Empress Agrippina the Younger , and maternal great-grandmother of the emperor Nero. Children with the Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt , the former lover of Julius Caesar: The twins Alexander Helios & Cleopatra Selene II . Selene married King Juba II of Numidia and later Mauretania ; the queen of Syria , Zenobia of Palmyra , is reportedly descended from Selene and Juba II. Ptolemy Philadelphus . DescendantsThrough his youngest daughters, Antony would become ancestor to most of theJulio-Claudian dynasty, the very family which as represented by Octavian Augustus that he had fought unsuccessfully to defeat. Through his eldest daughter, he would become ancestor to the long line of kings and co-rulers of theBosporan Kingdom, the longest-living Romanclient kingdom, as well as the rulers and royalty of several other Roman client states. Through his daughter by Cleopatra, Antony would become ancestor to the royal family ofMauretania, another Roman client kingdom, while through his sole surviving sonIullus, he would be ancestor to several famous Roman statesmen.TheBattle of Actium was the decisive confrontation of theFinal War of the Roman Republic. It was fought between the forces ofOctavian and the combined forces ofMark Antony andCleopatra. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC, on theIonian Sea near the Roman colony ofActium inGreece. Octavian's fleet was commanded byMarcus Vipsanius Agrippa, while Antony's fleet was supported by the ships of his beloved, Cleopatra VII, Queen ofPtolemaic Egypt.Octavian's victory enabled him to consolidate his power over Rome and its dominions. To that end, he adopted the title ofPrinceps ("first citizen") and as a result of the victory was awarded the title ofAugustus by the Roman Senate. As Augustus, he would retain the trappings of a restored Republican leader; however, historians generally view this consolidation of power and the adoption of these honorifics as the end of theRoman Republic and the beginning of theRoman Empire. Cleopatra VII Philopator(inGreek, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ; (Late 69 BC – August 12, 30 BC) was the last person to ruleEgypt as an Egyptianpharaoh – after she died, Egypt became aRoman province.She was a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty ofAncient Egypt, and therefore was a descendant of one ofAlexander the Great's generals who had seized control over Egypt after Alexander's death. Most Ptolemeis spoke Greek and refused to learn Egyptian, which is the reason that Greek as well as Egyptian languages were used on official court documents like theRosetta Stone. By contrast, Cleopatra learned Egyptian and represented herself as the reincarnation of an Egyptian Goddess.Cleopatra originally ruled jointly with her fatherPtolemy XII Auletes and later with her brothers, Ptolemy XIII andPtolemy XIV, whom she married as per Egyptian custom, but eventually she became sole ruler. As pharaoh, she consummated a liaison with GaiusJulius Caesar that solidified her grip on the throne. She later elevated her son with Caesar, Caesarion, to co-ruler in name.AfterCaesar's assassinationMark Antony in opposition to Caesar's legal heir, Gaius Iulius Caesar Octavianus (later known asAugustus). With Antony, she bore the twinsCleopatra Selene II andAlexander Helios, and another son, Ptolemy Philadelphus. Her unions with her brothers produced no children. After losing theBattle of Actium to Octavian's forces, Antony committed suicide. Cleopatra followed suit, according to tradition killing herself by means of anasp bite on August 12, 30 BC. She was briefly outlived by Caesarion, who was declared pharaoh, but he was soon killed on Octavian's orders. Egypt became theRoman province of Aegyptus.Though Cleopatra bore the ancient Egyptian title of pharaoh, the Ptolemaic dynasty wasHellenistic, having been founded 300 years before byPtolemy I Soter, a MacedonianGreek general ofAlexander the Great.[4][5][6][7] As such, Cleopatra's language was theGreek spoken by the Hellenic aristocracy, though she was reputed to be the first ruler of the dynasty to learnEgyptian. She also adopted common Egyptian beliefs and deities. Her patron goddess wasIsis, and thus, during her reign, it was believed that she was the re-incarnation and embodiment of the goddess of wisdom. Her death marked the end of thePtolemaic Kingdom andHellenistic period and the beginning of theRoman era in the easternMediterranean.To this day, Cleopatra remains a popular figure in Western culture. Her legacy survives in numerous works of art and the many dramatizations of her story in literature and other media, includingWilliam ShakespeareAntony and Cleopatra, Jules Massenet's opera Cléopâtre and the 1963 film Cleopatra. In most depictions, Cleopatra is put forward as a great beauty and her successive conquests of the world's most powerful men are taken to be proof of her aesthetic and sexual appeal. In his Pensées, philosopherBlaise Pascal contends that Cleopatra's classically beautiful profile changed world history: "Cleopatra's nose, had it been shorter, the whole face of the world would have been changed." ; Frequently Asked Questions How long until my order is shipped?

Depending on the volume of sales, it may take up to 5 business days forshipment of your order after the receipt of payment. How will I know when the order was shipped?

After your order has shipped, you will be left positive feedback, and thatdate should be used as a basis of estimating an arrival date. After you shipped the order, how long will the mail take?

USPS First Class mail takes about 3-5 business days to arrive in the U.S., international shipping times cannot be estimated as they vary from countryto country. I am not responsible for any USPS delivery delays, especiallyfor an international package. What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you givethat the item is authentic?

Each of the items sold here, is provided with a Certificate of Authenticity, and a Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity, issued by a world-renowned numismatic and antique expert that has identified over 10000 ancient coins and has provided themwith the same guarantee. You will be quite happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevantinformation and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing. Compared to other certification companies, the certificate of authenticity is a $25-50 value. So buy a coin today and own a piece of history, guaranteed. Is there a money back guarantee?

I offer a 30 day unconditional money back guarantee. I stand behind my coins and would be willing to exchange your order for either store credit towards other coins, or refund, minus shipping expenses, within 30 days from the receipt of your order. My goal is to have the returning customers for a lifetime, and I am so sure in my coins, their authenticity, numismatic value and beauty, I can offer such a guarantee. Is there a number I can call you with questions about my order? You can contact me directly via ask seller a question and request my telephone number, or go to my About Me Page to get my contact information only in regards to items purchased on eBay. When should I leave feedback?

Once you receive your order, please leave a positive. Please don't leave anynegative feedbacks, as it happens many times that people rush to leavefeedback before letting sufficient time for the order to arrive. Also, ifyou sent an email, make sure to check for my reply in your messages beforeclaiming that you didn't receive a response. The matter of fact is that anyissues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me. My goal is toprovide superior products and quality of service.

03379

Authentic Ancient Coin of: Mark Antony

Silver Denarius 17mm (2.60 grams)

Struck at Actium 32-31 B.C. for Marc Antony's Legion

ANT AVG III VIR R P C, Praetorian galley right.

LEG, Legionary eagle between two standards.