ATT. Namikawa Yasuyuki OLD Japanese Cloisonne Enamel Vase With PROVENANCE NO RES

Item History & Price

| Reference Number: Avaluer:161782 | Region of Origin: Japan |

| Maker: ATT. Namikawa Yasuyuki (1845–1927) | Age: 1850-1899 |

| Original/Reproduction: Antique Original | Primary Material: Cloisonne |

| Color: Multi-Color |

ATT. Namikawa Yasuyuki

OLD Antique Japanese Cloisonne

Enamel Vase with PROVENANCE

ATT. Namikawa Yasuyuki (1845–1927)

NEWARK MUSEUM PROVENANCE

ONLY .77 Opening Bid!!!

- NO RESERVE -

Currently, I am having my

"ECLECTIC EIGHT NO RESERVE FINE ART SALE"!

This interesting sale features an eclectic collection of 7 old,

antique and vintage impressionist, realist, expressionist & abstract

paintings and a vase with museum... provenance, in separate auctions.

Most of the art in this sale was done by listed artists and

hopefully there will be something in this sale for everyone!

Making this sale even better, ALL of this artwork is being offered with

only .77 opening bids, no reserves, no buyer's premiums and will be shipped

within 1 business day. Buyer’s will also only pay the actual shipping cost,

with no charge for materials, handling or transportation costs to the shipper.

Description

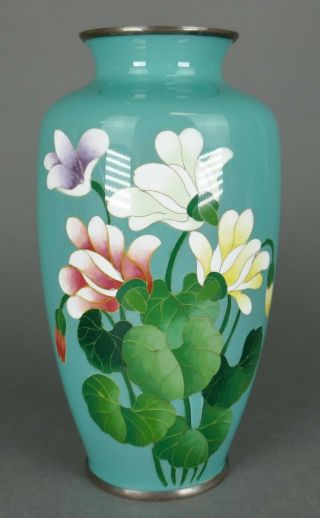

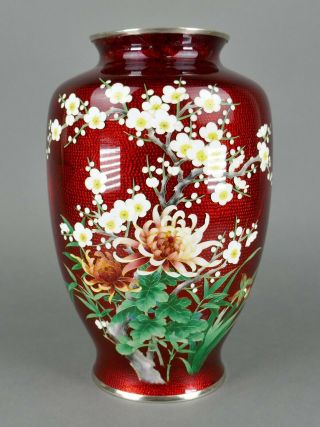

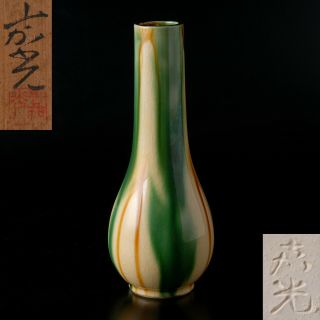

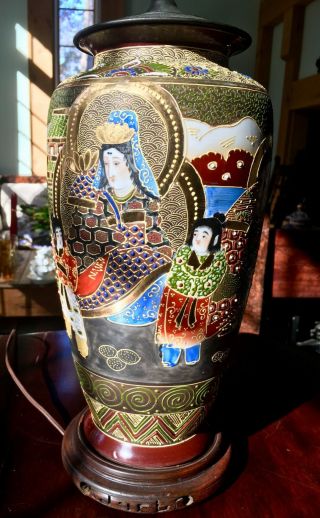

Item: ATT. Namikawa Yasuyuki OLD Japanese Antique Cloisonne Enamel Vase with PROVENANCE

Artist: ATT. Namikawa Yasuyuki (1845–1927) Please note that Namikawa Yasuyuki is also known as Yasuyuki Namikawa.

Provenance: Newark Museum. This vase was a part of a traveling educational cabinet of objects that curators of the Newark Museum took around to elementary schools to teach children about the method and scientific technique of enamel work in the 1950's and 1960's. Newark Museum's inventory numbers are on the bottom of this vase. Other provenance is with David Killen Gallery. Killen wrote an essay about this vase which is included below.

Signed: No.

Medium: Cloisonne & enamel vase.

Vase's size: 4.75" by 2.5".

Vase's Condition: Good, overall condition.

Ultraviolet Light Test: No restoration.

Special Shipping: Yes. Due to it's value and importance, it will be securely packed and shipped. Please note that I only charge the actual shipping cost or less and never charge for handling, materials or fuel.

Additional Comments: David Killen wrote the following about this important vase: "Japanese cloisonne vase, attributed to Yasuyuki Namikawa, ex collection-Newark Museum... showing the broken tile design, where the cloisonne has the beginning of a repeating tile design then stops, like a broken construction wall, that tells you that this is a work by Namikawa. No other cloisonne master in the Meiji period would make such a radical design at the time.

Yasuyuki Namikawa is perhaps considered the greatest cloisonne craftsman in the history of Japan. He has an entire museum dedicated to his work. From the important retrospective exhibit (Namikawa and Japanese Cloisonne), a retrospective of the artisan credited with popularizing Japanese cloisonne during the Meiji Era (1868-1912), contains a wealth of other unexpected exhibits jars with painterly landscapes, vases sporting understated compositions and containers with simple designs. It is these later works that best illustrate Namikawa’s innovative approach to cloisonne as an artistic medium, rather than as a purely decorative art. But even his earlier classic pieces, created for export during the height of Japonisme in Europe, displayed unusual features unseen in the Chinese cloisonne from which his craft derived.Perhaps being self-taught drove Namikawa to be extra meticulous and gave him the freedom to experiment. He was also fortunate to be working during a time of cloisonne revival spurred by the Meiji Restoration introduction of Western knowledge to industries. Paying heed to techniques and new enamels brought by government-employed foreign specialists, Namikawa was intuitive when it came to captivating an overseas market. His astonishingly intricate patterns surpassed that of his predecessors, while his development of vitreous enamels, polished for weeks to maximize luster, brought an unrivalled luxuriousness to the art form.At a time when 90 percent of Japan’s cloisonne was being exported, Namikawa was winning international prizes for impeccably executed designs and the inventions of two enamels: a translucent black, and a goldstone-like finish that shimmered with metallic dust. Overseas visitors, including Rudyard Kipling, even sought out his workshop to observe the painstaking process of detailed wirework, precise enamelling and conscientious polishing. In Japan, however, aesthetic preferences were evolving. As Kana Ooki, a curator of the Teien, notes in the exhibition catalogue, while the populous designs of butterflies, sprays of flowers and dragons continued to delight Europe, Japanese critics yearned for a revival of traditional and restrained artistry. At the 1889 National Industrial Exhibition, despite the acclaim he had received that year at the Paris Exposition Universalle, Namikawa was criticized for not looking beyond the classic use of elaborate motifs.As his home country became weary of Western influence, Namikawa’s works began to reflect an appreciation of traditional arts and crafts. The blank white space of the Incense Burner with Chrysanthemum Arabesques accentuates the vessel’s form, while in later works, he introduced nihonga-like (Japanese-style painting) landscapes, such as scenic views of Kinkakuji Temple and Kasuga Grand Shrine.Paring down the decorative elements did not, however, mean a lack of innovation. Namikawa continued to introduce new techniques, such as manipulating different thicknesses of wires to suggest painterly brushwork and using subtle enamel color gradations. By 1896 he had impressed enough people to be appointed an Imperial Craftsman to the Meiji Emperor, but by the time he had relinquished all decorative excess to settle on a style inspired by ink-brush paintings, the Western fixation on Japans arts had waned. The domestic market, unfortunately, was not enough to sustain Namikawa workshop, which eventually shuttered in 1923, just four years before he passed away."

Yasuyuki's vases are rare and very sought after by collectors. They can be found in the permanent collections of several museums and have sold for more than $200, 000, at auction. The provenance, age, design and superlative degree of workmanship this vase possesses are everything that you would expect and hope to see in a work by Yasuyuki. However, since the vase is not signed, I am only attributing it to Yasuyuki. I believe if you weigh the evidence, the evidence speaks for itself!

BIOGRAPHY:

Namikawa Yasuyuki (1845–1927) "From Around the World through Japan (Walter Del Mar, 1903): Y. Namikawa has long held undisputed supremacy as a maker of fine cloisonne; and we saw in his workroom different vases in the various processes from the one in which the metal ribbon is cut, shaped, and cemented over the minute design traced on the vase, to the final polishing up. Namikawa's production is a small one, but he boasts that each article is turned out perfect in every detail, and without a flaw. He used to boast that his work required no trademark or sign to distinguish it; but other makers have run him so close in excellence of work that he has been obliged to place a mark on the output of his workrooms. Although the cloisonne enamel is on metal, it is as easily chipped as porcelain, and it also requires careful handling to avoid tarnishing the metal cloison. The cloison is made on gold, silver, or copper articles with " wire, " or rather tape, of one of these metals, almost as thin as paper, and about one-sixteenth of an inch wide, cut of the required lengths, shaped with pincers, and cemented on edge to fit the tiny designs of flowers, birds, and other objects sketched on the vase or other article treated. When the interstices are filled with the various enamel pastes, and these have been burnt in the kilns and polished, the finished product turned out to-day by the best makers in Japan will compare favourably with that of any other country or time. Since 1860, when the imitation of Chinese models was abandoned, and designs from the best Japanese artists began to be copied in cloisonne, the manufacture has steadily increased in excellence, until it is now superior to any in the world. For the Chicago Exhibition of 1893 chased silver vases decorated with cloisonne and covered with a translucent enamel in beautifully-shaded, iridescent colours were first made, and for the Paris Exhibition of 1900 wireless cloisonne was produced by withdrawing the metal tapes after the cloisons are filled in with the enamels, and allowing the latter to coalesce. The result obtained is a shaded, or blended, instead of a well-defined, outline to the designs. From "In Lotus-Land - Japan" (Herbert G. Ponting, 1910): The art of making cloisonne enamel, whilst not modern, has yet been brought by a few of its present-day exponents in Kyoto to a state of perfection never hitherto attained by any one in this or any other land. In a short paragraph in Things Japanese Professor B. H. Chamberlain says: "The art first became known in Japan some three hundred years ago, but it has only been brought to perfection within the last quarter of a century. Mr. Namikawa, the great cloisonne maker of Kyoto, will show visitors specimens that look almost antediluvian in roughness and simplicity, but date back no farther than 1873." It was not, however, to Namikawa's that I first went. In other towns I had seen the process, and I had also visited several other makers in Kyoto before the above paragraph came before my eyes. When I read it I immediately arranged to visit the famous artist, and when my call was over I was glad I had seen the other places first, as I was thus better able to appreciate, from what I saw that day, the excellence of the workmanship which has placed the Namikawa product in a class which few of his contemporaries ever reach. It is not only his ware, however, that one goes to see, but also the unique and beautiful environment that this famous artist has created for himself. His surroundings and personality are so picturesque that the visits I made to his home will always remain amongst the most delightful of my memories of Kyoto. As I was whirled rapidly along in a rikisha, passing through street after street of two-storied houses with tiled roofs, each the exact counterpart of its neighbours, there was little outward show to indicate the treasures of art which might be concealed behind those wooden walls and paper windows. Indeed, the only visible clues to what investigation would reveal were often but simple boards on which were painted words in English such as "Komai", "Kuroda", "Jomi", etc. To the initiated, howxver, these words mean much, for they are, as already shown, names to conjure with in the world of art—the patronymics of some of the greatest artist-craftsmen the century has produced.

My sturdy little kurumaya, having received his instructions, hesitated before none of these, but trotted rapidly on until he finally turned into a quiet side lane in the Awata district, and with a jerk pulled up and dropped the shafts before a pretty private house. I thought there must be some mistake, but with a good-natured smile that covered his whole face, as he wiped the great beads of perspiration from his forehead and from amongst his short bristly hair, he pointed to a tiny placard, but a few inches long, by the entrance gate, bearing the simple inscription: "Y. Namikawa—Cloisonne." The door was immediately opened, and I was greeted with a "Good morning" by a young man who I learnt later was Mr. Tsuneki, Mr. Namikawa's brother-in-law. He conducted me past a pretty glimpse of garden into a room typically Japanese, except that it was furnished with a large cabinet and a graceful Chinese blackwood table. It was here I met Mr. Namikawa, a man of quiet speech and courteous manner, whose refined classical features betrayed in every line the gentle, sympathetic nature of the artist. The broad and lofty brow marked intellect and knowledge; his eyes were soft and tender, showing a kindly disposition, and as he talked they sparkled good-humour and the love of fun. His nose, which for a Japanese was large, but thin, showed good breeding and a sensitive nature, and under his well-formed mouth there was a broad but not too prominent chin. It was the face of a gentleman of culture and refinement. He spoke no English, but relied entirely on the services of Mr. Tsuneki, his interpreter, who invited me to partake of the tea which had been prepared immediately upon my entry of the house. Now Namikawa, like most of the present-day artists of Japan, has so far departed from the ancient traditions of his land that he makes no pretence of ignorance as to the object of one's visit to his house. There are still to be found in Kyoto, and elsewhere in Japan, a few of the old-time artist-craftsmen who cannot reconcile themselves to modern business methods, and with them the purchase of a small objet d'art may take an entire afternoon. The motive of the visit, although perfectly apparent from the outset, must be broached—or at least would be so by a Japanese, or any foreigner conversant with the customs of the land—in the most delicate manner possible; and only after much admiration and discussion, and careful expression and veiling of opinion, could a price be finally agreed upon at which the coveted possession would change hands.

There is none of this beating about the bush with Namikawa, however. He knows what you have come for, and he also knows that the average foreign customer is not overburdened with patience, and that the visitor may likely enough have planned to visit half a dozen other—I was about to say "shops, " but just checked myself in time—artists' houses the same afternoon. Namikawa is at the same time an artist and a man of business; therefore, whilst I sipped the tea, he set about the selection of sundry little boxes from a cabinet near by. When he had chosen about a dozen he placed them upon the table before me, and forthwith proceeded to open one. He produced therefrom a little bundle done up in yellow cheese-cloth. Removing this, there was yet more cheese-cloth, and after that a piece of silk. Unwrapping the silk, he disclosed to view a piece of cloisonne so exquisite in design and colouring that the finest I had hitherto seen seemed but crude in comparison. In turn he opened the other boxes, and as from each a fresh gem of art was brought to light I did not need to be told that I was in the presence of a master, for each was verily a masterpiece. There were tiny vases of which the groundwork was of yellow, not unlike Crown Derby; and others in their design and colouring at once suggested Royal Worcester, but that they were essentially Japanese. There were little jars and caskets of which the prevailing tints were delicate cornflower and peacock blues. There were groundworks of red and olive green, and there were others of ultramarine and deep purple. One and all, however, were decorated with designs more beautiful than any I had previously seen, and each was mounted on its own tiny stand of carved blackwood, as dainty in its way as the piece itself. Nowhere in Japan is it the custom to display the finest work at first. The Japanese knows as well as any one, perhaps better, that to show a fine work of art to the uninitiated is often but a thankless task—as indeed Kuroda had told me; therefore only where genuine interest and appreciation is shown, are the most cherished pieces brought to light. Besides, too, there is nothing the Japanese likes better than to have something still "up his sleeve, " and in this he shows a weakness that is, after all, but human and very Western. The visitor's knowledge and the value of his opinions are quickly gauged by these Kyoto artists. There is no deceiving them. No one knows more about the object shown than the man under whose supervision it was made. Pretence of knowledge is of no avail here. The real connoisseur reveals himself in every glance, just as the pretender betrays himself by every word. He who is anxious to learn, however, is gladly welcomed. Seeing my admiration, Namikawa produced other and larger pieces; but it was not until one of my further visits, several years later, that I saw the very finest possible examples of his skill—a pair of vases decorated with an old-time feudal procession, an order from the Emperor which had taken his foremost artist over a year to complete. The larger pieces were in no way inferior to the smaller ones, though the making of an absolutely perfect piece of large size is well-nigh an impossibility, as some tiny speck or minute flaw is almost certain to appear; yet careful examination showed that even in the largest there was such perfection as I had never seen before. I found that, as I had anticipated, each piece was valued much higher than any examples of the art I had hitherto seen, and if exhibited in any of the high-class shops of London or New York would probably command a price far exceeding its weight in gold. Incidentally it may be said that seldom, if ever, does the product of Namikawa's house appear in any shops. His output is so small that the demand for it from visiting connoisseurs and collectors is sometimes more than equal to the supply. There is no catering for the trade. That is left to those who have followed in the master's footsteps, who seek to imitate his methods and effects. As the pieces stood on the table they ranged in price from five to fifty pounds, a large piece of the latter value being about fifteen inches high, and decorated, on a deep blue ground, with a design of white and purple drooping wistarias. In this house, surrounded by so much that was beautiful in nature as well as art, each piece had greater beauty than it could ever have in a collector's cabinet, and it seemed almost sacrilege to remove any of them from the affectionate care of its creator and from the environment which became them so well. Whilst I was inspecting each vase, and casket, and urn in turn, Namikawa slid open one of the wood-and-paper shoji to admit more air, for the day was warm. Involuntarily glancing up, the beauty of the scene which met my gaze held me dumb with wonder and amazement.

Outside was a narrow verandah fronted with sliding windows of glass, and beyond was the essence of all that is aesthetic, restful, and refined in a Japanese garden. There was a little lake with rustic bridges, and miniature islands clad with dwarf pine-trees of that rugged, crawling kind that one sees only in Japan; and out over the water, a few inches from the surface, they stretched their gnarled and tortured limbs towards others of their kind which strove from the opposite shore to meet them. The house projected over the lake, and as my host stepped on to the porch the whole surface of the pond became as if a fierce squall had struck it, for from every part of it there came great carp, black, spotted, and gold, leaping and lashing the water to foam as they rushed literally to their master's very feet. He cast a handful of biscuits to them, and thereupon there ensued a frantic struggle and noisy sucking, as their snouts came to the surface gobbling up the tasty tit-bits. Handing some of the biscuits to me, he invited me to feed them from my hand. By lying down on the porch I could just reach the water, and I found the great beauties so tame that they readily took pieces from my fingers, and some of them would let me stroke them on the back. Under the shelter of a dwarf pine, on a tiny island in front, a little tortoise was gazing steadily at us. I threw a piece of biscuit to it, but it did not move. I tossed some more, but it never stirred. "Why doesn't it eat them?" I asked. Namikawa, laughing, replied, "It cannot eat. It is bronze." The picture was complete. Nothing was missing, and every detail evinced the artist's hand in composing it. Each shrub, each bridge, each stone lantern, and even each stone itself, was so placed as to help the composition of the picture. Had anything been added or omitted I believe the addition or omission would have been noticed. The thing was perfect. Here was surely the highest exposition of the landscape gardener's skill, for although the entire enclosure could not have exceeded thirty yards in length, and half as much in width, yet so clever was the arrangement of the water and the trees as to suggest a large area unseen, and even the trees themselves were so arranged and controlled in growth as to make the apparent size of the garden seem much greater than the real. Namikawa then invited me to inspect his workshop. Conducting me out into the garden and round the miniature lake, he led me to another building, which was open to the light on two sides, and furnished with running white curtains to soften and diffuse, if necessary, the strong glare of the sun. This was the workshop. I had not expected to see a large one, for in Japan such are seldom found, and many of the greatest masterpieces have been created in a little humble home, where a lone individual toiled week after week, month after month, and in many cases year after year, on a single piece, until the beloved thing stood at length complete—a master's work of art. I had heard of many such cases, and I was not surprised, therefore, to find Namikawa's entire staff in one room. Some weeks before, I had seen, in Yokohama, a cloisonne factory where the artisans worked on dirty wooden floors, designing and enamelling beautiful things—they seemed indeed most beautiful till I came to Kyoto. In other rooms figures, naked save for a loin-cloth, scrubbed, and ground, and polished huge urns, in some cases as big as the scrubbing figures themselves. And by the side of kilns, which gleamed dull red, old and practised men stood and watched, the sweat dripping from their half-nude bodies. And in Kyoto I had visited the Takatani factory, where an enormous demand for cheap ware from Europe and America is catered for—the work being done at rapid speed by young girls and children, who laid the enamel paste on with spoons, each completing many pieces in a day. These were "factories" almost in the sense that we understand the word, where the love of the lone individual of the old days, who wanted little and lived simply, content with the beauty created by his own hands—his craft his life and joy as well as occupation has degenerated into an imitation of the modern industrialism of the West, in the base desire for wealth which is sounding the death-knell of much that is best in Japanese art. But here were no such scenes. Instead, I saw a spotless room, twenty feet in length, the floor covered with padded mats, on which, bending over tiny tables, were ten artists, so intent on their occupation that our intrusion caused but an instant's glance. Close by them were two figures, rubbing and polishing.

This was Namikawa's entire staff. In this room could be seen the whole process by which the enamelled ware, called "cloisonne, " was produced, except the firing. Each artist was at work on some delicate little vase or dainty casket, which was surely, yet almost imperceptibly, assuming beautiful outlines and colouring on its graceful shape. At one table a bronze vase was receiving its decorative design, not from a copy, but fresh from the brain of the artist, who sketched it with a tiny brush and Chinese ink. At another table an artist was cutting small particles of gold wire, flattened into ribbon a sixteenth of an inch in width. After carefully bending and twisting the little particles to the shape of the minute portion of the design they were to cover, he then fastened them in place with a touch of liquid cement. At yet another table the wiring of a design had just been finished—the silver vase which formed the base being beautifully filigreed in relief with gold ribbon. Namikawa's fame rests as much on the lustre and purity of his monochrome backgrounds as on the decoration of his ware; therefore, this gold enrichment covered but a portion of the surface. It was simply a spray or two of cherry-blossoms, among which some tiny birds were playing. That was all ; yet even in this state, as it stood ready for the insertion of the enamels, it was a thing of beauty, for every feather in the diminutive wings and breasts was worked, and every petal, calyx, stamen, and pistil of every blossom was carefully outlined in gold, forming, for the reception of the coloured paste, a network of minute cells, or cloisons, from which the art derives its name. At other tables the enamel was being applied. The paste, with which the tiny cells are filled, is composed of mineral powders of various colours, which produce the desired tints, when mixed with a flux that fuses them in the furnace into vitrified enamel. In the finest cloisonne the cells are only partially filled at first. The piece is then fired. Then more paste is applied, and it is fired again. Perhaps it may be seven times treated thus before the final application of the paste, and this last coating is the most important. On it very largely depends not only the eiffect of the other coats, but also the appearance of the surface. It determines whether the surface shall be of flawless lustre, or pitted with minute holes. After this last filling and firing the vase presents a very rough appearance, for the final fusion has run the enamels together, as the cells were filled higher than the brim. There is little in its appearance at the present stage to indicate the beauty and brilliancy lying below. It is like a rare stone before it emerges from the hands of the lapidary. The vase must now be ground with pumice-stone and water for many days, sometimes for weeks, to reduce the uneven face to the same thickness all over. This is all done by hand, and calls for great skill and watchfulness, for were it ground thinner in one place than another the light would not be evenly reflected on the brilliant surface, and all the preceding work would be ruined. No turning-lathes are used for the work, though the device is well known in Japan. Gentle rubbing by hand is the only process employed. This grinding is accomplished so slowly that an hour's work scarcely leaves any perceptible impression. As the surface day by day becomes finer, pumice of softer and smoother quality is chosen, and the final pieces used are soft as silk. The pumice is followed by rubbing with smooth-faced stone and horn, and finally with oxide of iron and rouge, which gives a finish that has the lustre of a lens. Namikawa then makes his final inspection of the vase, though every day of its growth it has been under his watchful eye, and if pronounced perfect and worthy of bearing his name, it passes on to the silversmith for its metal rim round the base and lip, and to have the engraved name-plate attached to the bottom. On its return it is wrapped in silk and yellow cheese-cloth, and consigned to the cabinet in his house—not to remain there long, however, for it soon passes into the hands of some travelling connoisseur. On all the floor of this room, which was the birthplace of so many peerless examples of this art, now treasured in all parts of the world, one might search in vain for a spot of dirt, so cleanly is the process. One end of the room was shelved for the reception of the bronze and silver vases that are used as foundation for the enamel-work, and for some hundreds of bottles filled with mineral powders of every shade and colour. These were the materials for the enamel. The intimate knowledge of these powders can only be obtained by many years of patient study, for the colours change completely when in a state of fusion. Not only must the artist know exactly the shade of colour he desires, but how to obtain that colour ultimately by using one which is perhaps its diametrical opposite. Only by great skill and knowledge can confusion be avoided. Above the cabinet there was a foreign-looking clock, ticking off the hours and days, and sometimes years, that pass, as the works of art created here slowly assume the appearance which they will ultimately present to the world.

After inspecting the workshop I was shown the firing-room, and here, too, everything was clean and neat to a fault. There were two small furnaces, and in the centre of the room a brick platform on which a kiln could be rapidly made, from firebricks, for any sized muffle that might be desired. The bricks are arranged round the muffle, leaving a space of several inches to be filled with charcoal. Namikawa himself attends to the firing, perhaps the most important part of the whole process, for on it depends the success or failure of all the work preceding it. Any error in the degree of heat would ruin all. On the fusing depends not only the proper setting and colour of the enamel, but also, in a very large degree, the richness of lustre and freedom from air-holes in its surface—one of the principal beauties of the finest cloisonne. Namikawa told me that some colours present much greater difficulties than others to fuse successfully, and that large monochrome surfaces require more skill than small cloisons. He showed me one beautiful piece, of which the design was a maple-tree in autumn tints on a yellow ground. The grading of the colour and the veining on the leaves were exquisite, and had taken many days of care to prepare for the final firing and polishing. Apparently it would be well worthy of a place in his cabinet; but as the pumice ground the surface down, and the details became clearer day by day, unsightly marks began to appear, showing that it had been unable to stand the fiery ordeal, and had emerged from the kiln, not beautified, but marred and ruined beyond all hope. Thus it is that the finest specimens of cloisonne are so dear. The purchaser of the ultimate perfect piece must needs pay also for those ruined in the endeavour to produce it. Namikawa—this artist of such gentle appearance and manner—betook himself about thirty years ago to the manufacture of cloisonne, it having always been his ambition to become himself a master in the art of making the ware he loved. Only when the productions of his earlier days are shown can one see how great is the gulf he has bridged during that period. Each member of the staiF has absorbed the master's ideas from his earliest acquaintance with the art; and although Namikawa now does little work himself except designing and firing, he closely supervises each piece during its entire execution, and, if there be any cause for displeasure, sharply rebukes the transgressor for his want of care. During one of my subsequent visits to his workshop he detected a minute detail on a vase, in the hands ot one of the artists, that did not please him. His face became hard and stern, and his manner that of one who knows exactly what he wants and whose will must be obeyed, as he sharply rebuked the man for his lack of care.

His artists do not work by set hours, but only when the mental inspiration and desire for work is upon them. As this, however, is practically all day and every day, I have seldom, during my dozen or so visits, found a vacant place at the tables in the workroom. Namikawa divides with no one the honour of being the foremost cloisonne artist of Japan, and as the Japanese work is far superior to the Chinese—and no other cloisonne need be mentioned in the same category—the possessor of a piece bearing his name may rest happy in the knowledge that that mark stamps it as the best obtainable. From "Current Opinion" (Edward Jewitt Wheeler, vol. 11, 1892) In Kyoto we visited the studio of Namikawa, the greatest artist in cloissonne ware in all Japan. The Japanese name for this ware is shippo yaki. Namikawa was formerly a nobleman in attendance at the Court of the Mikado. His skill and love of art had led him to apply himself solely to his chosen occupation. All work is designed by himself alone, and nothing that is not perfect is allowed to leave the work-room. Not more than fifty pieces, large and small, are ever completed in a single year by him and his assistants, and sometimes the number is much smaller. All of his work is practically beyond value, and so highly prized that it is doubtful if at present there is a single specimen of the artist's ware in America. There are two other artists of the same name, one located at Nagoya and the other at Tokio, both pupils of the master, and, according to a Japanese custom, bearing his name. But the master is in Kyoto, and his works are priceless. In his studio we were shown two immense vases, replicas of two made for and now in the emperor's palace. They are for the fair. Two workmen have been constantly engaged upon them for the past year and a half, and expect to be another year yet in completing them. They are covered with most exquisite detail work, sharply defined by hammered copper wire. When all is done, there is still the risk of fracture of the enamel in the firing, and it is certain that if they are not absolutely perfect, Namikawa will not allow them to be shipped here. Neither his wife nor himself could speak any English and we but little Japanese; but "Hakurankwai, Chicago, " caused them both to beam with good nature; and after we had partaken of tea, kneeling in the Japanese manner while drinking it, we were shown many pieces of small ware, which were beautiful and artistic beyond description. The artist in Tokio has invented a new kind of cloissonne, whereby he almost entirely discards or completely hides the copper wires to hold the pattern. We saw one representing a cherrytree, the trunk of which was outlined by wires in bold relief, while the blossoms and leaves were soft and feathery against the background. The process is not known outside of this studio. He also reproduces old parchment pictures in a most delicate and exquisite manner, with tints of the ivory background preserved. We were shown a screen which was intended for the fair, but which the artist feared to send on account of the dryness of our climate, which would tend to check the material and destroy the article. The Japanese garden at the fair will be a revelation to the gardeners as to what may be done in prescribed quarters. While capable of beautifying nature on large scales, it is surpassing what the Japanese can do with the diminutive. Four feet square is a boundless vista to them and capable of great things in landscape-gardening. We have seen a parklet eight inches square in which there was growing dwarf shrubbery and flowers, and which was diversified with ponds, bridges, hills, paths, summer-houses, lanterns, and all necessary to the beautiful in the little. We wandered one day in a maple grove where no trees were more than an inch and a half high. We have seen dwarf pines six or eight inches high that were 125 years old, and others a foot high known to have existed for 500 years. Cherry and plum trees are cultivated in dwarf form for sake of the blossom only and not allowed to come to fruit. All Japanese are anxious to send to the fair something which will add to the honor of their country; but we found they were sorely afraid of enormous customs duties which might be charged by this country. We assured them to the contrary, as far as our limited knowledge extended, but were not sure how much ground they had for their fears. We were able to describe to them the lovely location which had been set aside for them– the island in the lake–and which coincides so thoroughly with their artistic natures. They have, notwithstanding their poverty, gone into this preparation for the fair with great zeal, and already their appropriations for expenses is one-third larger than contributed by England. All Japanese have a great desire to come to America, and we were besieged with applications to "please bring them over." They are an imitative race, and with the primitive means and clumsy tools at their command will successfully duplicate any work of other nations. Their methods seem to us as always beginning wrong end to, but the result is perfect. I could continue almost indefinitely describing what will be seen in the Japanese exhibit. A gallery of figures carved in wood, wonderfully life-like, and commemorating incidents and people, like Mme. Tussaud's in London; articles of bamboo and paper, of which materials it is said the Japanese can make anything under the sun; carved ivories, wonderful photographs, handsome lacquer-ware of new and surprising designs, elaborate embroideries, silver and bronze work–in fact, everything which the Japanese can make, and all of which are novel to this country, will be placed upon that little island, and show to the civilized world how far beyond them partially civilized Japan has gone in all the works of peace and industry. EXHIBITIONSParticipated in the following exhibitions:

1893: World's Columbian Exposition (Chicago, USA).

1900: Exposition Universelle (Paris, France). Was awarded the Gold Medal.

1903: The 5th Home Exhibition (Japan). Was awarded the First Prize.

1904: Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis, USA). Was awarded the Gold Medal.

1910: Japan-British Exhibition (London, Great Britain).Source: smokingsamurai

eBay SHIPPING POLICY: eBay now requires that I have to post a tracking number within 24 hours of receiving payment and has programming that verifies whether the item has been shipped. If you win more than one item on the same day I will gladly combine shipping, as long as it is not oversized. If there is any reason that your item should not be shipped immediately, please contact me before paying! If you find that there is a discrepancy between eBay's estimate and your invoiced shipping cost, please let me know prior to bidding. All packages are properly and professionally packed, as well as being insured. I always only charge the actual shipping cost or less and never charge for handling, materials or the cost of bringing it to the shipper. Please read all of the information below regarding the auction terms and I look forward to providing you with the best customer service possible.

PaymentSELLER'S PAYMENT INSTRUCTIONS:

Payment must be received within 5 days of receiving an invoice.

PayPal payments are preferred and if payment, or contact from the buyer, isn't received within 5 days, an eBay dispute will be opened.

This dispute will be closed within 4 days after being opened and the item will be relisted.

If you do not want your item shipped immediately (within 24 hours) please contact me before paying!

If you are interested in combining shipping with other items, please contact me before paying.

Once an item is paid for, I am obligated by eBay to ship it within 24 hours OR eBay marks it on my account as a transaction defect.

US BUYERS: The shipping calculator on the auction is an estimate and actual charges will be figured at the close of each auction. All residents within the state of New Mexico will be charged state sales tax (6.69%) at the time of checkout. If you can provide me with a copy of your NM sales tax ID, the sales tax will be removed.

INTERNATIONAL BUYERS: The shipping calculator on the auction is an estimate and actual charges will be figured at the close of each auction. Winning bidder is responsible for any brokerage and/or customs fee upon delivery. Import duties, taxes and charges are not included in the sold item price or current shipping charges. These charges are specific to each country and are the buyer’s responsibility. Please check with your country customs clearance office to determine what these additional fees will be prior to bidding/buying.

Shipping

SHIPPING & INSURANCE COSTS:

Service: USPS Priority Mail or FedEx Ground. Any item that sells for over $100 must be sent with signature required.

Shipping Address: If you pay with PayPal: I can only ship to the address listed on you eBay invoice & PayPal payment.

If you have a special address that your item needs to be shipped to, it must be reflected on both eBay & PayPal address, or I cannot ship it there. I am not protected by PayPal’s Seller Protection Policy if I ship to an address that is not reflected in eBay & PayPal’s system.

Estimated delivery: 3-10 business days after seller receives cleared payment. The estimated delivery time is based on the handling time, the shipping service selected, and when I receive the cleared payment. Country_cat777 is not responsible for shipping service transit times. Transit times may vary, particularly during peak periods.

I do not make money on shipping. I try my hardest to charge accurate shipping costs and to properly and professionally pack every item I ship!

I can use other carriers upon request. Other carriers and service may be more expensive and the buyer assumes all responsibility for the extra cost. I will gladly combine shipping if you win more than one auction that can safely be shipped together.

US BUYERS: The shipping calculator on the auction is an estimate and actual charges will be figured at the close of each auction.

INTERNATIONAL BUYERS: The shipping calculator on the auction is an estimate and actual charges will be figured at the close of each auction.

Winning bidder is responsible for any brokerage and/or customs fee upon delivery.

If you do not see a shipping quote listed for your country please send a message prior to bidding in order to obtain a shipping quote. Some items are Too Large for me to afford ably Ship Overseas and some items are forbidden.

Please understand that international shipping will cost more than domestic shipping and items could take awhile to arrive even when shipped the following day.

Import duties, taxes and charges are not included in the sold item price or current shipping charges. These charges are specific to each country and are the buyer’s responsibility. Please check with your country customs clearance office to determine what these additional fees will be prior to bidding/buying.

I always appreciate your business but U.S. law states that I must declare the actual value of any item that I sale, on the customs' forms. This is illegal and is against eBay’s policies. All items that sell for over $200 are sent via USPS Priority Int'l Express Mail. If you are an International bidder, please feel free to contact me for a shipping quote, prior to bidding.

Returns:

Please contact me if you have a question about an item before leaving a Feedback & DSR Star Rating! Everything I know about my items are described in the auction.

If an item has been broken during shipment, please let me know within 24 hours of receiving the item. I keep detailed digital photographs of all of the items sold and use third party verification.

If there is shipping damage, the winning bidder will need to hold onto all of the packing materials, and must wait for the outcome of the shipper's (FedEx / USPS) inspection, before receiving any money.

I use the highest quality packing materials & pack beyond FedEx / USPS standards. However, if there is damage during shipping, a return will generally require the buyer to forfeit the item to the postal carrier or to return it to the seller at the sellers cost.

If you have changed your mind, I ask that you pay for the return shipping.

Miscellaneous:

If the auction is described as having a frame, the frame is included. However, since some of the frames have per-existing damage (damage will be described in auction), please consider all of the frames in the auctions as being a free extra gift.